An interview with Giorgio Santoriello, author of Colonia Basilicata

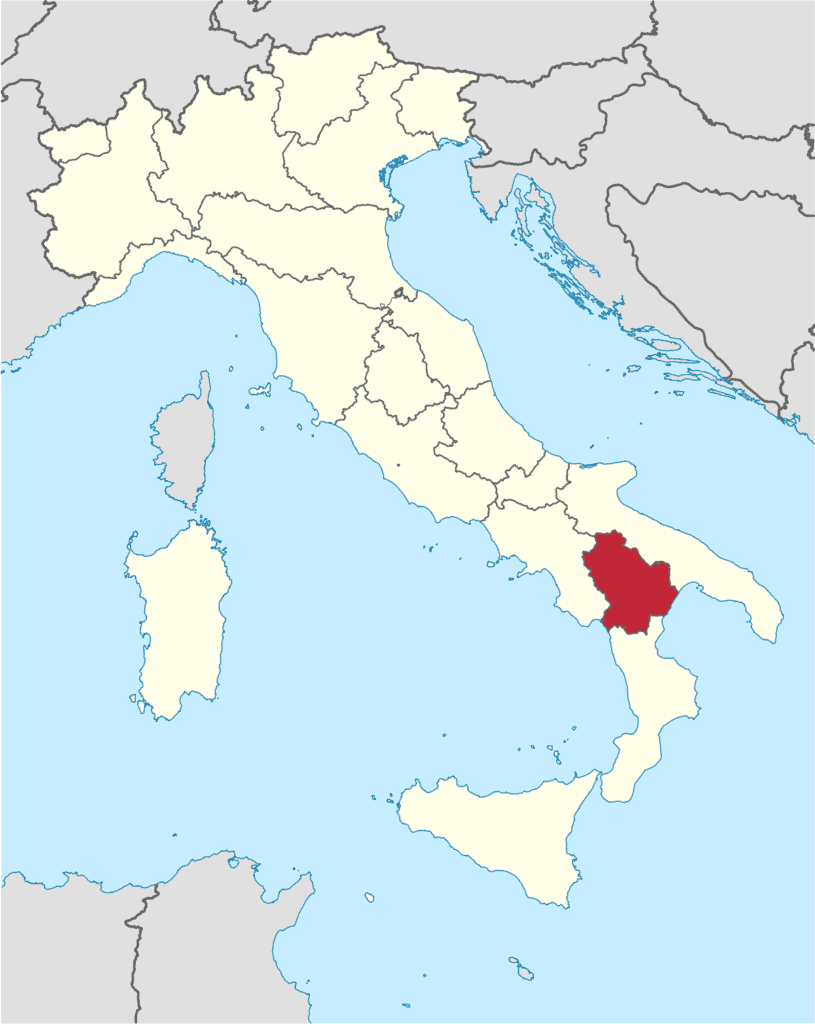

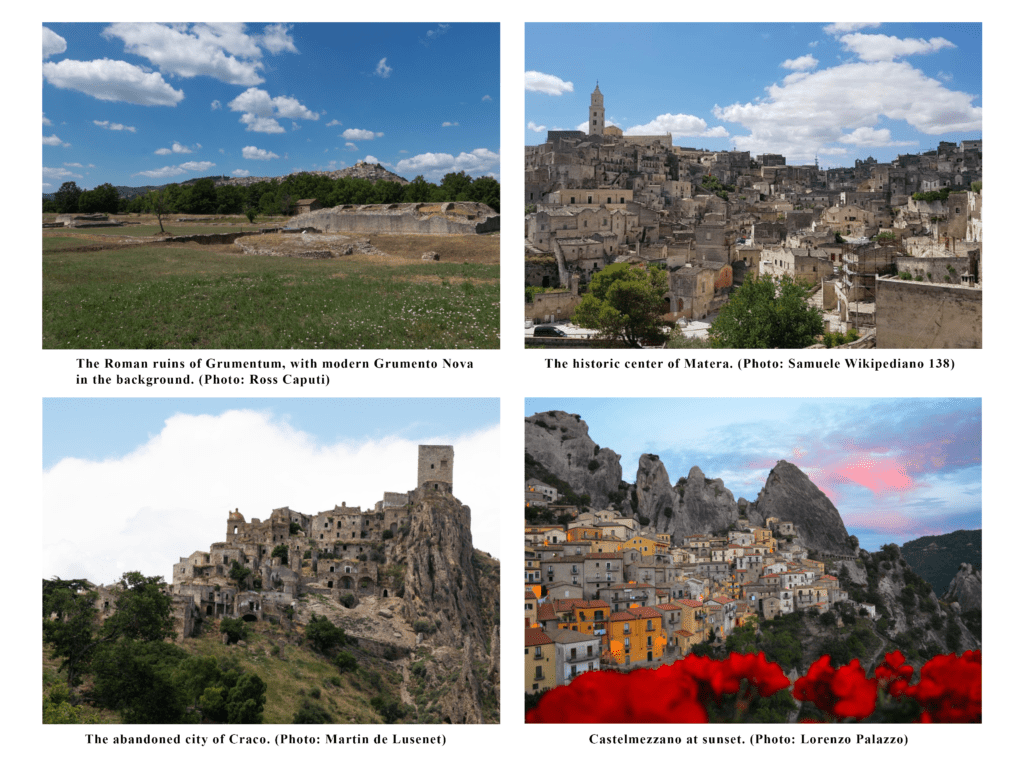

The region of Basilicata is historically one of the poorest and most rural regions of Italy. With a total population of only half-a-million people, Basilicata is known to outsiders for its vast landscapes, its picturesque villages, and its many heritage sites: The Sassi of Matera, the abandoned city of Craco, the beauty of Castelmezzano, and the Roman city of Grumentum. But behind the postcard images is the toxic reality of the oil industry in the region, which has an environmental track record that borders on the criminal. The areas most impacted by the oil extraction have seen sharp rises in the rates of cancers, yet Eni, the petroleum giant, exerts undue influence over the region’s economy and political process, allowing them to avoid accountability and oversight.

In this interview Pummarolə speaks with Giorgio Santoriello, journalist, author of Colonia Basilicata (2020), and Founder of COVA Contro, a grassroots organization that does environmental analysis to combat the eco-mafia.

Pummarolə: Before we get into your work, could you tell us a bit about where you were born and what your childhood was like?

Giorgio: I was born on December 18th, 1983 in Policoro, on the Metapontine coast. My family, like most others in town, was not originally from Policoro, though. My grandfather was from Canosa and was working as a Marshal in the Carabinieri, but he decided to retire in Policoro.

When I was a kid I remember Policoro being more green and less built up than it is now. We spent most of our summers at the beach, but I also worked in the fields when I could, a habit that I kept up even after I started working in seasonal tourism. I remember lots of open spaces, the feel of the Magna Grecia heritage that surrounded us, a still living memory of the post-war agrarian reforms, and good years and bad years with the economy, which left their marks on the city, like with the case of the famous sugar factor that cut the city’s beachfront in half. As kids we were always playing in the streets and during the summers we outside all day long. Piazza Heraclea was the main hangout spot, but within the span of just a few miles we had fields, hills, and the beach. At least until I was 18 I remember a Basilicata felix, but then I started at the university in Matera. I began reading the local newspapers and that opened up a new world for me and began a new phase for my adult life in which I shed the romanticized ideas I had and developed a more critical love for la mia terra.

Pummarolə: Why did you choose to become a journalist?

Giorgio: Around 2010 I decided to work as a freelance columnist because my generation didn’t have a voice in the local newspapers. The average age of most journalists was over 50. In college I became outspoken about local politics and about the policies of the University of Basilicata. Later I became a youth activist with the political party, Alleanza Nazionale, and then, unfortunately, I got involved with Il Popolo della Libertà. But even though I enlisted, I never became a full card-carrying member because I was very critical of the factional leadership. Eventually I realized that what was lacking in our newspapers wasn’t just the voice of my generation, but real investigative journalism, the kind that searches for inconvenient truths. At that point I transitioned from being a polemicist to documenting what was actually happening on the ground.

Pummarolə: When did the oil extraction in Basilicata begin? And at first how did people feel about it?

Giorgio: There were a few exploratory wells being drilled in the Val d’Agri early in the 20th century, but that came to a halt during WWII, and then started up again with the Italian oil company Agip, which later became a subsidiary of Eni. This exploratory phase began in the late 50’s, taking place mostly in the eastern part of the region between Ferrandina and Pisticci. Then the real industrialization began in the Val Basento, with extraction wells and gas pipelines, and the creation of ANIC (Azienda Nazionale Idrogenazione Combustibili) and the Pozzi company. Then in the 80’s and 90’s there began a second wave of drilling and a build up of infrastructure, which in some ways is still ongoing with a number of pending projects.

The political and business communities have all lined up in support of the slogan that Basilicata is the “energy hub” of the south. Meanwhile the attitude of the public hasn’t really changed since the 50’s. There were timid and limited protests at first and a few last ditch efforts to resist, but the local population has never really united against the oil industry. In fact, it has gone on to drill 430 more wells and to build three more industrial centers, an underground storage facility, and a waste disposal center, while dumping petroleum waste products into at least two wells, burying hundreds of kilometers of pipelines, and producing a quantity of waste products that have never actually been measured. The local population doesn’t matter in the eyes of our political leaders, and this was confirmed first by presence of nuclear plants in the region and later by the oil industry.

Pummarolə: When did people start to realize that the drilling was polluting the environment? And how has ENI responded to the reports of rising cancer rates in the region?

Giorgio: There are now numerous studies that attest to the degradation of the environment and the reduced quality of life and life expectancy. The Istituto Superiore Sanità (Higher Instituto of Health) reported in 2011 rises in mortality for numerous types of tumors, from stomach cancer to leukemia, and rises in diabetes as well as heart and respiratory pathologies, even among children. Professor Bianchi of the Center for National Research (CNR) in Pisa reported excess mortalities among women living in Grumento Nova and Viggiano, which indicates that the emissions from the COVA (Centro Olio Val d’Agri) plant in Viggiano as a primary cause. However, the politicians ignored the results of the study and no one ever replicated it.

A few years ago the CNR found the air quality in Viggiano near the Eni plant to be comparable to the air quality in Vienna. So, the industrial center from a small town with 5,000 inhabitants produced the same air quality as the Austrian capitol with 1.5 million inhabitants. Over the years at COVA Contro, we found an abnormal presence of hydrocarbons in the milk from local cows and also in the ground water, not to mention the pollutants discovered in the fish from Lake Pertusillo. The omissions in public oversight are all premeditated. In fact, they have a singular purpose: To allow the oil companies to do whatever they want to do.

At this point the local population knows that the oil industry is a terrible neighbor, just totally unaccountable for a number of reasons. Fortunately, there is now a healthy amount of distrust towards the oil industry, but it’s not enough, because Eni extorts the population by offering jobs and money. The government has unfortunately incentivized this form of socioeconomic extortion by legalizing a system of environmental compensation. The oil companies confer royalties to local governments, even in anticipation of future damages. This has undermined the foundation of our democracy and our constitution, because for us conflicts of interest and a lack of transparency have become the norm. Oil companies respond to these problems by promising money, jobs, and development, promises that in reality never turn out the way we hoped. They trade the compensation they pay out for our broken dreams and aspirations, deceiving and lying to us because they know there will be no consequences for them. Everyone knows that the oil industry enriches a few and creates huge problems for everyone else, but there’s no collective will to come together and resist. Unfortunately, I think we will realize what we’ve lost only after it’s too late.

Pummarolə: Can you explain the work that you’re doing with COVA Contro?

Giorgio: In order to confront this mare magnum of problems, in which business, politics, and the mafia are all intertwined, I decided to found COVA Contro in 2013. It provided a platform that, through critical thinking and data-driven investigation, I could document the effects of the oil industry in Basilicata. The press wasn’t investigating anything, least of all conducting real interviews. The politicians are all enthralled with the oil industry, business leaders are blinded by profit, and even the church is silent on the destruction of the environment, making it clear that the celebrated Laudato Si is not coming to Basilicata. Today COVA Contro provides technical support to the victims of pollution, in the form of chemical analysis and legal resources. We document the environmental impact that the officials have failed to take notice of, we put pressure on the judiciary, and we’re trying to turn public opinion around, the youth included, and unite the people of Basilicata.

Pummarolə: How does the situation in Basilicata compare with other communities around the globe that have fought against the presence of pipelines or extraction plants?

Giorgio: The entire network of pipelines, from Viggiano to Taranto, is more than 130 kilometers, and it was built without any opposition from the local population. There was no serious movement to block or boycott the project. Meanwhile in the US, you had strong, sustained protests against the Keystone pipeline, as well as a public debate. In Basilicata, with the exception of a few citizens and a handful of associations, the politicians and the business community couldn’t wait for the pipelines to be built, which officially had only two spills and Eni claims that they were caused by sabotage. To this day there is still no transparency about where exactly the pipelines run or how they’re maintained, and they haven’t even finished paying out the remittances for the massive spill of crude oil in Bernalda. We just don’t know the pressure or the condition of the pipelines, or the exact quantity and chemical composition of the crude oil that’s being piped through the countryside. And we’re not even sure if there is a reliable public monitoring system. As always, Eni is only accountable to itself.

Basilicata could maybe learn something from Nigeria, where a significant part of the population rose up, some armed and others just protesting, against the presence of the oil industry in their country. Because here 99% of the population is either indifferent or on Eni’s payroll.

Pummarolə: What about the international community? Have they done anything to help or hurt the situation?

Giorgio: There is a strong American presence in Eni. Between Black Rock and Goldman & Sachs, 17.9% of Eni’s capital is either American or Canadian. But also Halliburton has tested several drilling muds and drilling fluids in the wells here. Total, Newark, and Schlumberger have contracted with Eni to develop horizontal drilling, while finding ways to avoid paying for the lands that they occupy. And then there are the American universities: MIT, UC Riverside, and Harvard all came to Basilicata to confirm Eni’s position, saying that it’s safe to dump waste into the wells as long as they reduce the quantity. They didn’t say a word about the waste coming back up, or the contamination of the aquifer, or the dangers of subsidence or seismic activity. And we have no way of knowing how much funding Eni provided to these experts or what other conflicts of interest there might have been. But while these American experts were telling us everything was fine, a number of Italian scholars and former employees of Eni were saying that this practice of dumping waste into the wells is absurd!

Let’s help Giorgio keep doing this important work by donating to COVA Contro here!