Some explanation of our name

by Samantha Pinto, on behalf of Pummarolə

July 31, 2020

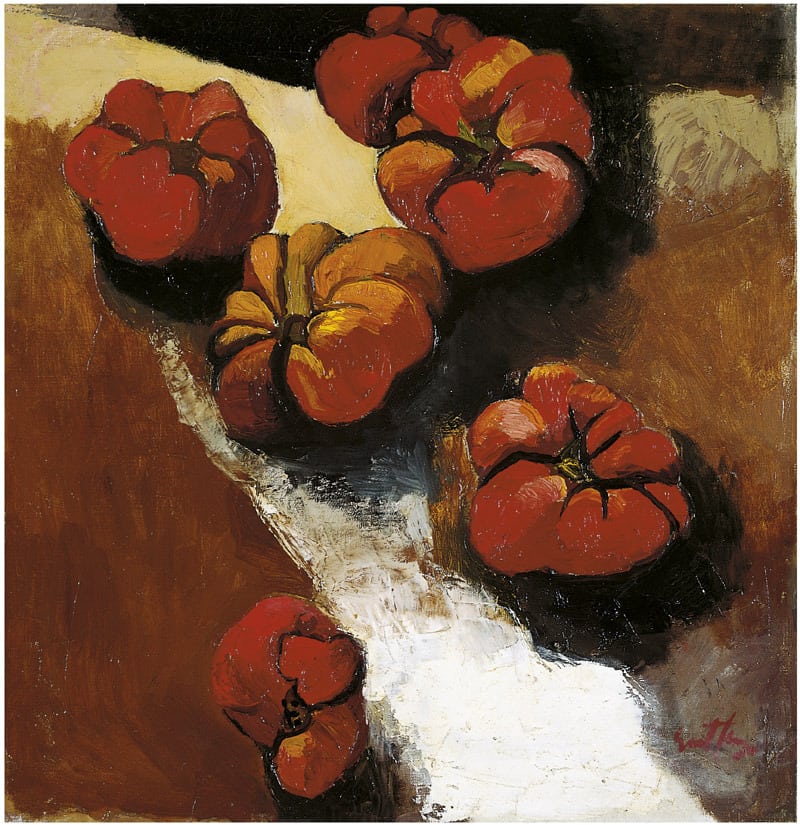

Pummarola is the Neapolitan word for tomato. What food staple is more emblematic of the Italian Diaspora than the tomato? It is the basis of gravy (otherwise known as “pasta sauce”) whose acidic-garlicky scent wafts through the streets of South Philly every Sunday afternoon. The tomato, despite being native to Central America, has become the basis of our peasant dishes, our street foods, and our comfort foods. Like the Italian diaspora, it’s a fruit that has been contested, mischaracterized, and sometimes maligned; yet, it has also become a part of the American mainstream. Beyond mere symbolism, the history reflects our contradictory material relationship to capitalism, imperialism, and the institution of whiteness. Following the trajectory of the tomato from its native Central America to Europe and back to North America can provide an alternative framework for understanding our history and identity, in contrast to the current narrative dominated by the veneration of figures like Christopher Columbus.

What if we discarded the “Great Men of History” paradigm that wastes so much time weighing the words and deeds of individual men like Columbus? We chose the name Pummarolə because we want to talk about the material realities of our ancestors in Italy and in the settler colonies that allowed them to build comfortable lives in the diaspora. Let’s talk about the poverty, the exploitation, and the hardship, but also the rebellions, the strikes, and the uprisings. Let’s talk about our current position within capitalism and settler colonialism today, and start using our time and energy to align ourselves with oppressed people, rather than continually debating the legacy of Columbus ad-nauseum. Instead, let us ask what is the reality of this legacy of colonialism?

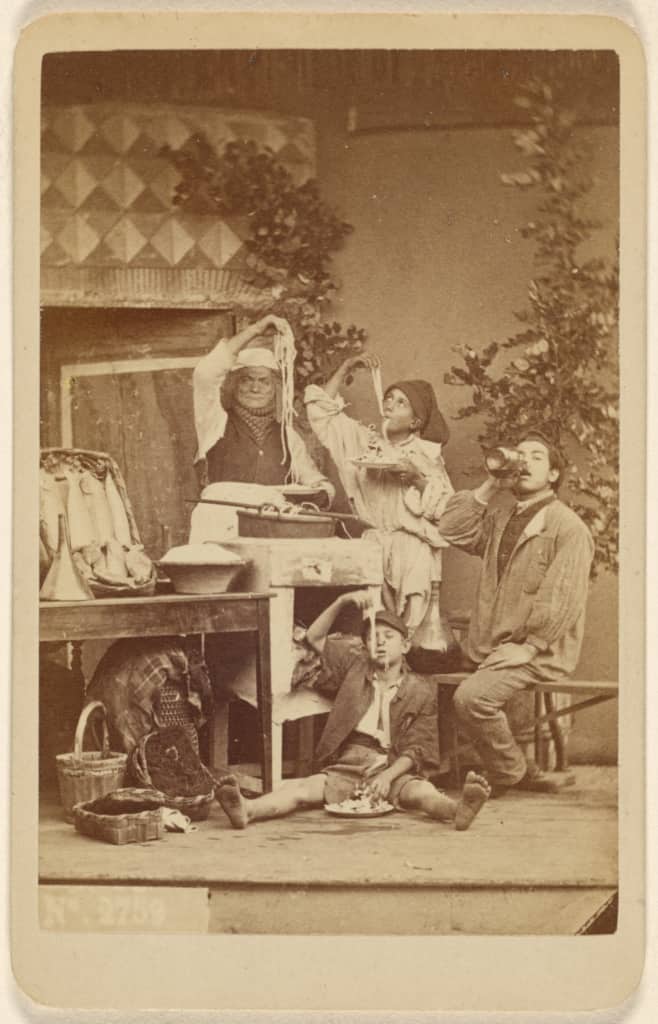

The tomato made its way to Italy vis-a-vis the Spanish empire following Hernan Cortes’ genocidal conquest in the Americas. The tomato is indigenous to Central America but was not a significant staple to the Aztecs at that time. It took several centuries for the tomato to integrate into Italian cooking. Throughout Northern Europe, the tomato was misclassified for a long time as a toxic plant, associated with deadly nightshade, and largely grown as an ornamental plant; this was in part due to the European elites’ tendency to use lead plates, which reacted with the acid in tomatoes. Italians began consuming tomatoes in the 15th and 16th centuries; the first documented recipe comes from the memoirs of an official cook to the Spanish viceroy in Naples. The tomato eventually became a staple to both the peasants and the urban underclass, whose diets already consisted of mainly vegetables and wild greens. Here the tomato connects, indirectly, two somewhat different classes of subjects in the Spanish empire: the indigenous people of the Americas who were decimated by war and disease, whose lands were stolen and exploited, and whose societies the colonial powers and Catholic church attempted to destroy altogether, and the masses of peasants and urban poor whose land and labor were exploited to enrich the Spanish imperial crown, and whose uprisings were often repressed with great brutality by the Spanish.

In one way, the oppressed classes in Italy—often represented as “peripheral” to Europe, or in the words of Temple University professor Peter Gran, “defectively” European—benefitted from the so-called Columbian exchange. The Spanish conquest of the Americas devastated the land and indigenous peoples of the Americas, enriched the colonial elites, and simultaneously provided a source of subsistence and comfort to its oppressed subjects back in Europe. Peasants and the urban poor in Southern Italy had to contend with natural disasters, feudal and neo-feudal exploitation, taxation, foreign domination, and political repression; and the tomato allowed for the development of satisfying and cheap dishes like pasta al pomodoro and pizza. As Italian American herbalist and artist Samantha Blancato has noted, the peasants because of their connection to the land recognized the tomato as an edible and valuable crop, unlike the elites who grew them as ornamental plants and discarded them at the end of the season. The tomato would soon become central to the peasant’s everyday life. In the rural South, the preservation of tomato paste in the sun for use year-round became an iconic summer ritual, one that would later be transplanted to the Little Italies following mass emigration.

When millions of Italians left the peninsula for settler colonies like the United States, Canada, and Australia as well as Latin American countries like Brazil and Argentina, our ancestors could experience creature comforts never imagined in their home villages. It is true that they were exploited in Italy by large landowners and foreign rulers, and after 1861 the nascent Italian state was rife with its own national contradictions. And when they immigrated to places like the U.S., they were treated as racially inferior immigrants, sources of cheap labor, criminals, and political subversives—not unlike non-white immgrants today. Just as European elites had decried their heavily vegetable-based diets in Italy, some American social workers considered the practice of drying out tomatoes in the open air to create paste as “unhygienic,” as noted by Jennifer Guglielmo in Living the Revolution. But despite their exploitation and subalternity, these immigrants were eventually able to purchase land and foods in a way they could never imagine in Italy. For the first time meat was affordable enough to eat regularly throughout the week, not only on holidays– and furthermore, Anglo-American social workers encouraged the integration of meat into the Italian immigrant diet. As a result of all this our bisnonni began incorporating meat– beef, pork, sausage, and meatballs– into our infamous Sunday gravy. Within a few generations due to a combination of (often forced) assimilation and identification with institutions of white supremacy like the police, Italians were able to integrate into the fabric of mainstream America.

Many reactionary Italian Americans like to point out this history of subjugation and subalternity as a way to undermine contemporary struggles against poverty, discrimination, and racism. Just as people love to counter “All Lives Matter” to the affirmation that Black Lives Matter, the story of Italian immigration is weaponized against oppressed people today. On immigration: “our ancestors came here legally and accepted American culture.” On anti-black racism: “Italians were treated badly and got over it, why can’t black people get over slavery?” On Indigenous Struggles: “Native Americans have casinos and land, Italians had to work for our money. What are they complaining about?” Not only are these arguments usually completely false, but these ahistorical myths oversimplify the complexity of our history and divide us from those resisting oppression today.

The reality is that many things can be true at once; Italians can be oppressed by colonial and capitalist elites and simultaneously benefit materially from imperialism. Our great-grandparents and even maybe our grandparents may have faced racism, may have been exploited for cheap labor, and deemed biologically inferior to Anglo-whites. But it is also true that they made decisions over the years to align us with the institution of whiteness. Journalist Adryan Corcione makes the point that we need to look at this history through a dialectical lens by examining opposing forces: in this case, the historic exploitation of our immigrant ancestors is opposed by our community’s participation in oppressive systems in order to access the material benefits of whiteness. Like other groups of “white ethnics,” many Italian Americans fought to exclude Black workers from unions, opposed integration of public schools, joined white vigilante mobs and picked fights in black neighborhoods during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. And while Italian Americans were often the victims of police repression in earlier decades, many joined the ranks of law enforcement; by betraying fellow workers, protecting private property, and participating in an institution historically rooted in the slave patrols, Italian Americans were able to assimilate and build comfortable middle-class lives in post WWII America. In a society where human lives matter less than profit, whiteness has become synonymous with the ownership of private property. That being said, many of our ancestors rejected this system altogether, fighting and sometimes dying for the cause of human liberation.

Our ancestors over generations did not passively accept exploitation, though the dominant liberal paradigm of history often reduces Southern Italians in particular as passive “subjects.” Millenarian movements throughout the Middle Ages, though often dismissed as primitive or fanatic, gave voice to disenfranchised peasants who saw a new world just on the horizon. Throughout Spanish rule in Southern Italy there were frequent rebellions in both cities like Naples and the countryside, like the revolt of Masaniello in 1647 and the short-lived democratic revolution of the Parthenopean Republic in 1848. Heterogenous bands of rebels, peasants, and former- Bourbon soldiers known as briganti resisted the annexation of the Italian South during the Risorgimento, the movement to create the modern Italian nation-state lead by middle-class intellectuals; in turn, the nascent Italian army engaged in brutal repression and collective punishment of entire villages in the South. In the decades after Unification, peasants, farmers and sharecroppers throughout Sicily organized “fasci siciliani” throughout the 1890s and rose up against the perennial agrarian crises at the advent of capitalism in Italy. As immigrants after Italian unification, both to Northern Italian industrial centers and settler colonies like the U.S., Italians were among the most militant anarchists, syndicalists, and socialists. They created a vibrant world of resistance and mutual aid guided by the spirit of rebellion and the vision of a better world just on the horizon. Repression of leftists during the Red Scare, the rise of Fascism, and the dominance of the liberal paradigm in mainstream discussions of Italian history have over the years relegated these histories to obscurity.

There is also a relatively small but vocal Italian American elite which claims to speak for all of us by promoting a whitewashed version of our history, in which downtrodden immigrants pulled themselves out of poverty and discrimination by sheer entrepreneurial will. Organizations like UNICO, NIAF, and the Orders of the Sons of Italy have chosen to dedicate an inordinate amount of resources and time defending Columbus. In generations past, the prominenti of Italian American communities actively supported the Italian Fascist Party and, for example, held rallies in cities like Philadelphia in support of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Again today, these self-appointed spokespeople attempt to drag all of us to the wrong side of history. That being said, a growing number of us have been challenging these reactionary narratives for years. Italian American workers, scholars, artists, activists, and healers are committed to the legacy of our ancestors who fought and died for liberation. And as we grapple with our position as settlers in a world where the contradictions of capitalism only intensify, we know this fight has a long way to go.

Even today, the tomato is at the center of this struggle. As Italy is both a country of emigration but simultaneously a “destination country” for migrants and refugees from Africa and Asia, it struggles to contend with its colonial past and own crises. In the past few decades, reports have surfaced of modern-day slavery for migrant agricultural workers throughout the South. Predominantly African immigrants travel from region to region, following the seasons, endure mafia-brokered exploitation and violence. In 2010, following the shooting of two undocumented African workers, race riots broke out in the small Calabrian village of Rosarno. Of the Rosarno Riots, Roberto De Robertis has written that,

“like Calabrian peasants in previous decades, the Africans decided to rise up against their bosses and exploiters, refusing the conditions that were imposed on them… With these events, African peasants gave a collective response to an individual act of violence, giving new meaning to political struggles in the regions of southern Italy.”

Even a decade later, hundreds of thousands of precarious migrant workers struggle against absurdly low wages and racist violence.

First and second generation children of immigrants also struggle with racial discrimination and questions of assimilation, just as our bisnonni did in the U.S. generations ago. There is also an entire generation of Black Italians who have lived their entire lives in Italy yet do not have citizenship rights. Italy follows a jus sanguinis citizenship model that bestows these rights based on blood rather than birthright: ironically, many Italian Americans are eligible for Italian citizenship based on their ancestry, while children of immigrants who were born and raised in Italy are not. Italians, including Afro-Italians, have taken to the streets not only in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S, but also to highlight Italian racism against Black people, migrants, and refugees in Italy. These activists have sparked an important conversation about what has been forgotten about Italy’s past, to all of our detriment in the present.

In many ways these are conversations that have already been going on for decades, perhaps only in small circles or academic works. But today, in many cities Italian Americans and Italian Canadians have begun challenging the mainstream narrative about Columbus and aligning with broader struggles for justice. In this current historic moment, we have an opportunity to connect with each other and amplify this history. We also have an opportunity to honor our ancestors who fought for human liberation by today fighting in solidarity with Black and Indigenous-led movements, as well as confronting violence against women, queer people, disabled people, immigrants, and workers. Let’s give up the spaghetti dinners of the past, and the Columbus festivals where we don tricolore-beaded necklaces and tacky “100% Italian shirts.” Instead, let us acknowledge the material comforts we have been granted at the expense of other people’s humanity and commit to fighting for that better world our revolutionary ancestors saw on the horizon.

This essay is cross-posted in our About Us section.

“Italians were among the most militant anarchists, syndicalists, and socialists.” <–YES true but often forgotten! That's the legacy we must honor. Fighting for each other, fighting for disenfranchised lives, fighting for progress…

You’re so right! It is definitely not something I learned in school or even in university Italian Studies classes, until I went out of my way to do my own research. Recently I have been really enjoying “Living the Revolution” by Jennifer Guglielmo and “Italian Immigrant Radical Culture” by Marcella Bencivenni which help reconstruct this history.