by Mike Fiorito

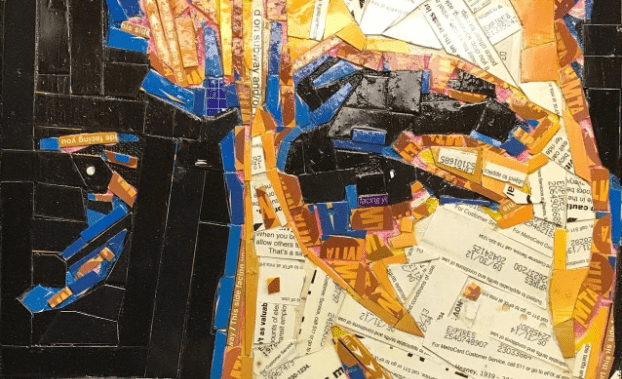

I first put Ernie Paniccioli’s name to his face when I saw Juan Carlos Pinto’s portrait of him hanging up at OYE Studios in Brooklyn. There are always many artworks on display at Pinto’s studio. Some are completed projects; some are works in progress. But this portrait really spoke to me. The hint of a smile, but yet the face wasn’t smiling. The eyes looked welled up with tears, but they weren’t crying. Pinto managed to express a living essence behind the eyes in this portrait.

“Who’s that,” I asked.

“Where have you been? Living under a rock, bro?” he said, laughing. Then he told me it was Ernie Paniccioli, or Brother Ernie, as he’s also known.

Ernie was born in Brooklyn, of Cree Native and Italian American parents, and grew up in a tough section of Bedford Stuyvesant. Because he looked Native, he was called “spic” and “Geroninmo.” He was once chased after and beaten until he had blood dripping down his face. Discovered on the ground in this state by members of the Bishops, a local gang, he was promptly asked to join them.

Ernie soon found his way out of this world, moving to Greenwich Village where he discovered a whole new universe of art and culture. It was in Greenwich Village that Ernie became friends with Richie Havens, who at the time was mainly a painter.

Then, in 1965, Ernie joined the U.S. Navy. After leaving the navy, he began experimenting with photography on the streets of New York and documenting the beginnings of Hip Hop culture. By the 1980s, Ernie was a sought-after photographer in the music industry. In 1987 he became the principal photographer for Word Up! and Rap Masters magazines, and his work began appearing regularly in publications such as Vibe, The Source, Rolling Stone, and The Village Voice. His photographs tell the story of Hip Hop culture’s evolution from the 1980s through the mid-2000s, and have been the subject of numerous gallery shows, along with the books Who Shot Ya?: Three Decades of Hip Hop Photography (2002) and Hip-Hop at the End of the World: The Photography of Brother Ernie (2018). With Ernie’s blessing, Cornell University compiled an archive of Ernie’s photographs and made them available to the public. How often does an artist like Ernie make his art available to the world for free?

I had the pleasure of speaking to Ernie on a Saturday afternoon in February 2021.

“In Hip-Hop at the End of the World you wrote that graffiti wasn’t always pleasant for regular hardworking people who rode the subways. Sometimes they couldn’t see their stop because the windows were marked up.”

“Let’s face it, not all graffiti artists were Dondi. There was some beautiful work, but a lot of it was shit, too.”

I told Ernie that, when I was a kid growing up in the Ravenswood Projects in Queens, some of the guys I knew that did graffiti seemed to have a death wish. I remember Mike Ferrone climbing up the grating on the Scalamandre edifice in Long Island City. He made crazy faces and, dangling fifty feet in the air with one hand holding on the grating, he sprayed WC (Wild Child) on the Scalamandre bricks with the other. Then there was NESS, who hung upside down in impossible positions, tagging building walls, and subway platforms. Most people couldn’t understand how someone could tag a piece without using scaffolding, or something to stand on. They were miracle acts. We looked up, as if to the heavens, to see their art. And when the train cars whooshed by with their names, we were all proud to see their works. Doing graffiti was about being seen. Your work moved on trains around the city. Standing out above them all, in our circle, was Louie (KR.ONE) Gasparro. Coming from the artistic traditions of Dondi and Don1, Louie’s work was visionary.

I told Ernie that I wasn’t an expert on Hip Hop and or rap, though Ravenswood was just up the block from Queensbridge, one of its epicenters. We talked about some of the rap artists that we both really admired, like Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest and Nas.

“Those guys had a message,” said Ernie. “And the fact is, the government was scared shit of them. They called out injustice. And their lyrics were brilliant. They poked fun at the idea that African American artists were just supposed to make happy music and not shine a light on the struggle of racism and oppression.

“What do you think happened to rap?”

“I think the violence and glorification of guns fucked it up. When the lyrics went from depicting injustice and oppression to expressing bravado and talking about violence for violence sake, the music lost something.”

“What do you listen to now?”

“The truth is I mostly listen to jazz: Coltrane, Miles, Sun Ra, and Ornette. And I recently rediscovered Pharaoh Sanders. Man, that cat doesn’t get enough credit.”

“You’ve mentioned that now you’re a Zen Buddhist.”

“My interest in Zen stems from my interest in martial arts. The Buddhist monks learned martial arts to de-escalate attacks on them. When I was a kid, I studied Soo Bahk Do, Korean Karate, which is more about blocking than striking; that said, the blocks are also strikes.”

I could see how Ernie’s combination of experiences enabled him to gain trust with rap, Hip-Hop and other artists. Many of these performers were from the streets. They weren’t going to let just anybody take pictures of them. It had to be someone that knew where they came from. And you can see Ernie’s inner humanity in the photos he took, capturing not just the celebrity of rappers like LL Cool J, Naughty by Nature, Public Enemy, and 50 Cent, but their essence, too.

“I really love some of the jazz elements in early rap,” I said.

“You kiddin’ me? That’s my favorite. You have to include Guru with his Jazzmatazz albums. Of course, there is a Tribe Called Quest. It’s funny, Q-Tip told me that some cats thought the original jazz artists that he sampled had stolen the parts he sampled from them. I laughed.”

“Q-Tip was providing an education to people. I’m sure a lot of people went back and checked out the original jazz recordings,” I said.

“Q-Tip is one of those people who transcends his art and tries to offer something to the world. This is what I relate to most.”

“How did you learn about your Cree ancestry?”

“My mother was Cree. But by the time I came around, so much of our history was lost.”

“Was there a point when you had a revelation about your Cree origins?”

“It didn’t mean anything to me. As a kid I only knew Mohawks; there were a lot of Mohawks in New York City. They worked on the rigs, building the skyscrapers. Looking Native has always defined my life. It meant something in a way to me that’s hard to describe. Like it’s in my bones. Then, in 2009, I was brought up to Canada for an event. When I arrived, there were fifty Cree people at the airport to greet me.” Ernie paused and took a breath. “They were grateful that a Cree had done so much. That meant a lot to me.”

“One thing that really comes across, Ernie, is that you have so much love in your heart. Where did you get that from?”

“That comes from my mother. Maybe this is the Cree heritage she passed on to me. She taught me to approach people with love. I try to alter their perspectives. Once they understand who they are they understand who I am. It just feels right to be right and do to right. I always feel dirty after conflicts. Also, studying Zen has taught me things. Zen gets into the essence of balancing everything out. What’s relevant. What’s real. What’s magical.

I could tell by talking to Ernie and what I’ve read about his life that he learned his big love from knowing pain. No doubt his stories of growing up as an outsider, getting his ass kicked in tough neighborhoods taught him that no one should feel that kind of pain. Not all people that come from tough situations come out of it with love. But when they do it’s called wisdom. When you look at the eyes on the portrait that Pinto did of Ernie, you can see something of the life that he’s lived. That portrait is a window into Ernie’s big soul.