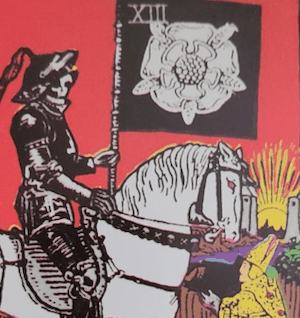

She starts to turn up the cards. Diamond, spade… Death!

We first see him shirtless, effortlessly lifting a dead tree. He stares into the camera while breaking down a wardrobe with his bare hands. He takes a selfie, full center, his muscles bulging under a too tight button-up, Elisa’s quirky smile just an afterthought to the left of the frame. Picture after picture, we learn to know him as a good giant, a good guy who was love-struck. He was enamored, in tears, obsessed. He was a good person, naïve, clueless, just wanted to help. He was a small-town Rambo and so very likable. Liked. We hear nothing of her. She is at the edges, small print to his front page titles. She only exists through him: his obsession, his unrequited love. On the last Sunday of August 2019, 28-year-old Elisa Pomarelli had lunch in a trattoria near her hometown with a long-time friend, Massimo Sebastiani. Then, she disappeared. About two weeks later, Sebastiani confessed to killing Elisa and led the authorities to the retrieval of her body, which he had hidden in the hills near Piacenza. It was for love.

Diamond, spade… Death! I read it clearly… me first.

What’s in an honor killing? Dante tells us that, Boccaccio tells us that. She provokes, she errs; he kills. While the Italian law that guaranteed lighter sentences in the case of honors killings was abrogated in 1981 (with law 442, which eliminated both honor killings and matrimoni riparatori, by which a case of rape was solved with the forced marriage between perpetrator and victim), it has left persistent traces in the conceptualization of such crimes. The victims’ lives and conduct are consistently and deliberately investigated in all their aspects, with any behavior or characteristic that is perceived as non-normative becoming an alleviating circumstance. The killers are normalized, good men who didn’t mean any harm.

Enters Carmen.

Olga Matei was strangled in 2016 by Michele Castaldo: she had been seeing him for a month and he was jealous over her not dating him exclusively; she appeared unyielding to his complaints. During Castaldo’s trial, a life sentence turned into 30 years, then 30 years were reduced to 16, a sentence that can be further shortened for good conduct. Again, we hear his motives: in his psychiatric report, we read that he was undergoing an overwhelming emotional and passionate storm (“una soverchiante tempesta emotiva e passionale”), a condition that was found to be “eligible to have an influence on his penal responsibility” (“idonea a influire sulla misura della responsabilità penale”). Obsessed, jealous, haunted: a novel Carmen, she provokes him. She then disappears behind the curtain. We read the names: Elisa, Olga, Angela: alluring, highly-sexualized characters (no longer individuals) whose deviant behavior compels the male co-protagonist to kill them. The curtain falls, people clap. The crisis-woman from fascist propaganda leaflets is subdued, the she-wolf from Italian realism is tamed. Mothers are safe, family values preserved. Until women err. In early 2018, 19-year-old and homeless Jessica Faoro was stabbed by a man who had offered her shelter. In the press, we learn about her drug abuse issues. Her homelessness becomes central.

She shuffles the cards. Again! Always Death!

Carmen haunts us as the other: minority women, such as Moldavian Olga Matei, are shown as unreliable, too free sexually, and overall provoking the anger of the average Italian male. This becomes more accentuated when foreign women are also sex workers. In such cases, the murders are dismissed quickly and rarely gain much attention at all. “Who is going to cry for Benedita?” (chi piangerà per Benedita?), wrote novelist Igiaba Scego in an April 8, 2019 social media post, referring to the murder of Nigerian sex worker Benedita Dan, killed by 41-year-old Leopoldo Scalici in Modena. In her post, Scego reflected on how the murders of non-Italian women, and of sex workers in particular, are treated as irrelevant or even expected and deserved, and asked readers to “cry for our sisters.” The murderers belong, their behavior and lives normalized via interviews with neighbors and family members, comments on academic background or social status. The murder then becomes an exceptional fact, a sudden and unexpected variation from a regular life pattern, and thus more excusable, or even understandable. Obsessed, mad, but a good guy after all.

Donatella’s wild eyes still staring at us from the trunk: in the 1975 case known as the Circeo massacre, we have the most extreme example of normalization of the killers. Donatella Colasanti and Rosaria Lopez, two working-class teenagers, were abducted, raped and brutally tortured by three young men belonging to the richer strata of Roman society, Gianni Guido, 19, Angelo Izzo, 20, and Andrea Ghira, 22. The promise of a party. I imagine the car ride, then the country villa. The smell of cigarettes, the guys acting nice, joking around. Then the threats, the tortures, Rosaria drowned in a bathtub, Donatella pretending to be dead. Her last words in 2005: “Let’s fight for the truth.” Even amid protests, with some papers addressing the status of the perpetrators (Guido was the son of a banker, while Izzo and Ghira, who had connections with neo-fascist associations, belonged to upper strata of the Parioli neighborhood) and the power imbalance between aggressors and victims, the outcomes were relatively positive for the three murderers. The three upstanding boys (“ragazzi perbene”) walked into the court self-assured. Izzo smiled frantically. While they all received life sentences, not one of them completed them. Ghira managed to escape to Spain and allegedly died in 1994 of a drug overdose (there are later sightings, reports). Guido’s sentence was converted to 30 years, allegedly because of a donation his family made to Rosaria’s family, and escaped twice, spending the years from 1985 to 1994 in Panama before being recaptured; currently, he is free. Izzo, released in 2004, immediately killed two more women and is currently serving life for these later crimes.

I’m imploring, beseeching / our past, Carmen – I forget it!

The rhetoric of the upstanding young man from a solid family, taken over by an unexpected criminal raptus, has also been central in articles on the murders of Alba Baroni, shot in 2007 by her long-term boyfriend, 22-year-old Sara di Pietrantonio, whose ex-boyfriend strangled her and then set her on fire in 2016, and many others. The attackers’ social class and status still play a role in their representations in the press reports. Again, the common trope of the good guys overcome by obsession for the victims return invariably.

Take up the packs and let’s go. The curtain falls a last time.

Note: The segments in italics are fragments from Bizet’s libretto, taken out of order and randomized, and from the many articles on the cases being investigated. Together, they unsettle the discourse and open the perspective to different narratives.