by Charles Tocci

The movement to remove Columbus statues has much to learn from the long history of Black activism and its efforts to create a more truthful and inclusive public history. While the removal of Confederate monuments became a flashpoint during the summer of 2020, Black organizers had focused their efforts on these statues for over a century. Their experiences offer a deep catalog of strategies and insights from which to glean.

For over a century, Silent Sam, a statue of a Confederate soldier, had stood watch over the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Campus. It was erected in 1913 with support from the United Daughters of the Confederacy and was dedicated to the “young student soldiers who went out from this grand old University to battle for our Southern rights and Southern liberties.” Left unsaid was the fact that Carolina students lost their lives to preserve the Southern right and liberty to enslave African Americans.

When UNC racially integrated in 1960, on-campus resistance to the monument began with protests and defacement. In the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, protesters gave Silent Sam a paint job in the orange, red, yellow, and green colors of the Pan-African flag. The pushback reached a crisis point in 2017, when Emil Little splashed Silent Sam’s pedestal with a mix of red paint and her own blood. The response from the university and the community to the latter was swift and lopsided: Pro-Confederate protestors were allowed on campus and protected by the same campus police who harassed anti-Sam demonstrators.

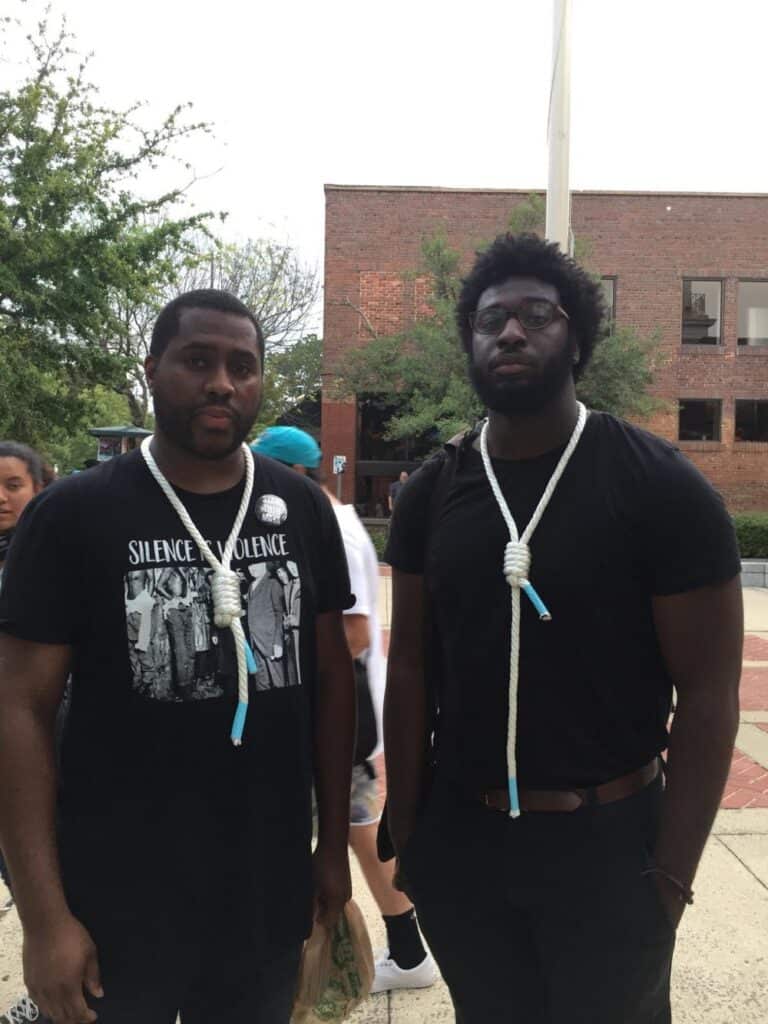

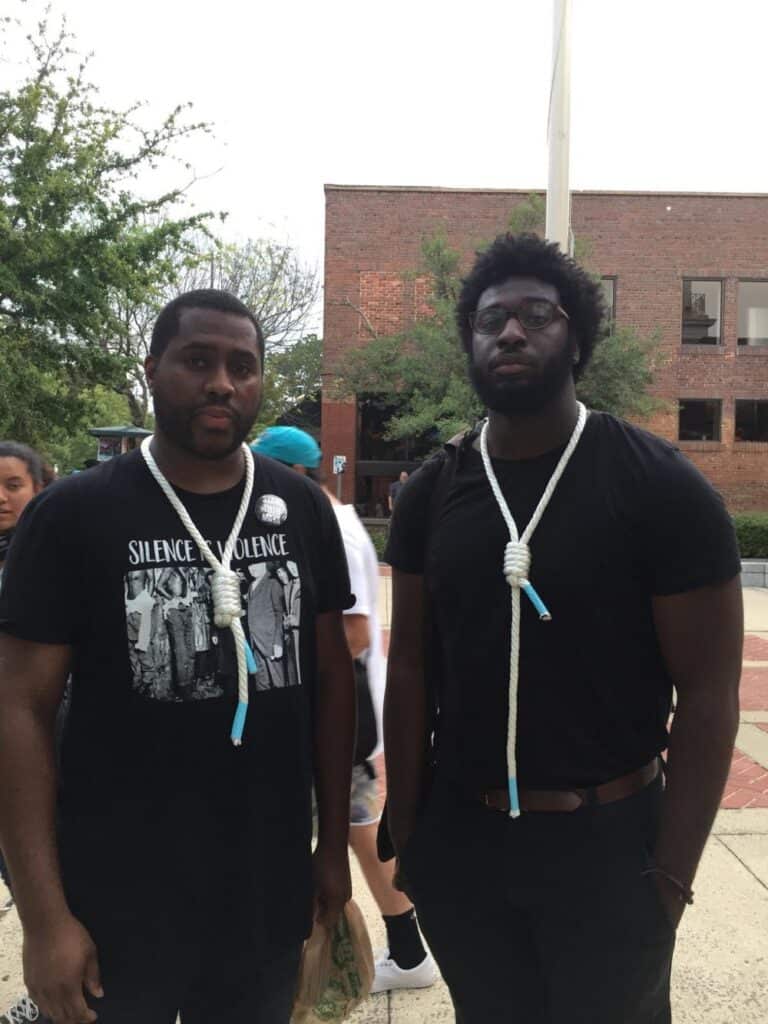

In the middle of these convulsions and as a living protest, UNC doctoral students Jerry Wilson and Cortland Gilliam began to wear nooses around their necks with Carolina blue aglets attached. Wilson hit upon the idea when reflecting on what Confederate statues mean to Black people and researching prior historic campus protests where Black students also wore nooses in a call for anti-lynching laws.

The furor over Silent Sam was enough to force the university to remove the statue and see its chancellor resign, but the memorial’s fate remains uncertain. The initial plan to move the statue to a new on-campus “education center” at a cost of $5 million drew heavy criticism. The next proposal was to donate the statue to the Sons of Confederate Veterans, along with $2.5 million for its “care and preservation,” but last year a judge ruled against this plan. As of now, Silent Sam sits in darkness in an undisclosed location.

In light of the growing movement to remove Columbus statues, I interviewed Wilson to gain insight into effective, powerful protests that can lead to the removal of racist monuments. His efforts show us how much imagination is needed to connect history with the present and do so in symbolic and action-oriented ways. This is a lesson we must learn if we hope to create a public history that challenges white supremacy and builds a landscape that fosters justice and solidarity.

Our interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Tocci: You’re a native Tar Heel. How did you feel about North Carolina growing up and what did you learn about its history?

Wilson: So I learned about all of the state items: the dogwood, the cardinal, the state vegetable, and all those things that stuck with me. What I remember most about the state is how many songs there are. One comes to mind, ”nothing could be finer than to be in Carolina.”

You know I look back on it now it kind of feels like propaganda, but I genuinely believed North Carolina was a special place on this earth. I’m sure most states are like this, but the social studies curriculum is very North Carolina-centric in the early grades. I learned a little bit about some of the Native communities in North Carolina but not too much. It’s always past tense like the really, really old past tense, pre-Trail of Tears.

Did that change to a more complex history as you moved into high school?

Somewhat. I remember taking Advanced Placement American History my junior year. We had a great teacher who was very charismatic. I remember he came to school dressed in complete Civil War garb. And his coat wasn’t blue.

But I do remember having seen Roots. I do remember learning about the Civil Rights Movement, of course, because my parents were in the Nation of Islam. I had probably more exposure to some Black nationalists through the mosque my family attended. It wasn’t until I got to undergrad and beyond that I really learned about some of the key figures from Charlotte who were huge in the Civil Rights Movement and beyond.

I went to Fayetteville State University, an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), so African American history was a required course. It was really, really eye-opening and set the stage for the rest of my time at this historically Black college that was founded in 1867.

What’s the public history look like on the Fayetteville campus?

My freshman year I stayed in the building Vance Hall, named after Governor Vance who fought in the Civil War and probably was a slaveholder.

I’ve heard you talk before about the special place that the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill holds in the state of North Carolina. What drew you there?

The prestige. This is a big deal. This is UNC-Chapel Hill, you know! The world-renowned institution, mostly for basketball, but the research is important, too.

There’s a school of government there that trains elected officials from around the state. Chapel Hill has a special role in public service. But when I got there I realized that that was not the case at all, partly because of the conservative takeover of the state legislature that had been underway for years by the time I arrived.

This institution and somewhere, deep down inside it was my love for this institution and the role that it plays in the state. This is the university of the people. Or so it claims to be.

Before the protest started, what did Silent Sam mean to you?

Not too much. I remember there being some controversy around one of the buildings on campus being named after a klansman. There was an effort to change the name of the Saunders building and students were lobbying to make it Zora Neale Hurston Hall. And the university ended up changing the name to Carolina Hall. I later found out that there was a group of students who stood out on the front steps of the building with nooses around their necks in protest of the name.

Silent Sam stood not too far from the School of Education, so I would see students sitting out here at all times of the night. People would go and donate food and cases of water to students who were out there protesting. And that was when I really became aware of the statue and its meaning and history and thought seriously about it.

It wasn’t just their student protests and sit-ins. It was the fact that the university tried to infiltrate those protests with an undercover police officer. One night, they sent in an undercover police officer who student protesters had seen in uniform by the statue to pose like a mechanic.

How did you decide to make your protest and what kind of hopes and fears did you have going into it?

The actual catalyst for me was Emil Little, a student in the history department, who put a combination of red paint and their own blood around the base of the statue. She was arrested and charged with damaging state property, but also with an honor code violation.

I remember going to the courthouse and the student activists organized around her. I remember sitting in the courtroom and just thinking, “How many injustices have happened in this courtroom over the years?” And I started thinking about how the university could punish somebody for supposedly defacing the hate symbol, and I tweeted this, “What would happen if somebody brought a noose on campus?” How could the university credibly punish the students who brought the noose while at the same time protecting and spending lots of money on a Confederate statue, which has the very same messages and links?

And then I was like okay, I don’t want to hang a noose on campus, but what if I brought a noose to campus on my person? What if I wore noose? I sat with that for a little bit and I went and spoke with a colleague of mine, Cortland Gilliam who’s another graduate student. We’re sitting in my office and I said, “what if I wore a noose on my neck on campus in protest of the statue?” He was like, “Oh wow! That’s heavy.”

We talked initially about how to not be offensive to other Black folks in the space and particularly older African Americans for whom this symbol still carries additional resonance that we aren’t even aware of because it’s not as visceral for us not having lived through those periods of history.

So, then, we started doing some research trying to find some historical precedent and discovered the protest at Howard University in the 1930s, a silent anti-lynching protest, where students and professors lined the sidewalks wearing nooses around their necks. When I found that I was like, okay, I feel better. You know, like other folks have done this. It’s not disrespectful. It is sincere, but it’s also extreme, right. It’s intended to point out how extreme it is to have Confederate monuments on the campus of an institution of higher learning in 2018.

What were the reactions like?

Initially, there weren’t very many. It was a lot of eye avoidance. There were double takes but like silence. But I will say that you know more people looked at me when I was wearing the noose than when I wasn’t. We had one person walk up to us and ask, “What are you guys doing?” Initially, I was thinking that we would be inundated with people wanting to talk, so I had made up these little cards that explained this is a protest that you want to learn more and go here. But surprisingly, very little engagement.

There was one reaction that I did get most often walking across campus and it was like snickering usually from young white men, which annoyed me. I couldn’t tell if it was like nervous laughter or meme culture—this urge to point and laugh first before any attempt to understand.

What have been the long-term repercussions since then?

When we made the short film (Black Out Loud) in September of 2019, we walked into the chancellor’s office wearing the noose and the staff was like, “Hey, can I help you? What are you doing?” But we got a meeting with the chancellor that same week to screen the short film we made just by interviewing Black students. We had people answer a few questions about their experiences of being a Black student on campus and Cortland edited that together into an 11-minute short film that we screened on campus.

I remember being in the Faculty Council meeting when Chancellor Folt was trying to decide what to do about the statue. It was like a free-for-all, with lots of upset faculty and students lining the edges of the room, and I remember asking her, “What does Silent Sam mean to you?” She said, “Well, I think it means the same thing that it means to all of you.” And I followed up, “What is that?” Her aides were trying to jump in and break up the moment, but she answered before they could. She said, “I think it means white supremacy.”

Right then and there, that was the end of her tenure, because the folks who were lobbying for the statue to remain that’s what they didn’t want to be acknowledged publicly. That’s what the statue stood for, what we all knew.

Here’s the person in power is who says the quiet part out loud.

That was also the one that got the most coverage on the news. An undergraduate student who’d won the Martin Luther King Jr. Award that year basically stood up and said, you know I’m embarrassed to receive that award.

In hindsight, what does Silent Sam mean to you?

It means exactly what the noose means—it’s a threat in support of white supremacy.

Statues have multiple meanings and as much as we like to think about the meanings changing over time, their constituencies stay. I’m reading Karen Cox’s book No Common Ground. She talks about protests against Confederate moments and the “Lost Cause.” She talks about a statue of John C. Calhoun in South Carolina and about how initially, there was one that was lower to the ground and there are these oral histories from Black folks at the end of the 19th century who, whenever they knew they were walking past that statue, they would take a handful of rocks or something with them to throw it and try to take the nose off.

Silent Sam always meant intimidation and fear and white supremacy to Black folks in the Chapel Hill community, especially when we learned about the speech given at the statue dedication and where the speaker is bragging about horsewhipping a Negro right in front of the statue for having disrespected a Southern lady. For anyone who’s been listening and paying attention, the statue’s meaning hasn’t changed. Most of it is about white supremacy and our refusal to publicly acknowledge that and accept that. It’s bewildering.

I want to make the shift over here to the Columbus statutes. For folks who are advocating to bring them down, what kind of insight can you share?

When we talk about Columbus statues, folks have to ask the question of those who are in support of the statues remaining, “What are you gaining from the statues?” I don’t think we asked that enough. I think a lot of times we put the burden on the challenger and not the incumbent. But I think we should reverse it and say, what is it that you gain from this without a selective memory?

We should think very seriously about erecting statues to anybody, but definitely, we should question whether the statues that are standing should remain because those statues have always had multiple meanings depending on the figures represented. They’ve always maligned some groups and antagonized some groups. The question is, do those groups have the power, political and social power, to do anything about it?

In a lot of ways, the answer to that question is almost always the same—it’s that we can’t allow this history to be forgotten. When we listen to Confederate sympathizers it’s, well we can’t allow the sacrifice of the South to be forgotten. And when we listen to pro-Columbus people, a lot of it is, we can’t allow Italian Americans and Italian American contributions to this country to be forgotten. It’s this investment of the whole of an identity into one figure, which is also known to be antagonistic. It’s known to be offensive and it undercuts the entire identity by making it toxic.

I thought about the question, what should we do about the statue? What if we take them down? What should go in that place? How can we contextualize them? I have thought, what if besides every statue of a person who held slaves we put a statue of someone in bondage suffering with the cattle brand or something like that. Is that erasing history or adding more history in context? I’m sure that the folks who support the statue would say no, that’s not the type of remembrance that we want. Folks are advocating for a certain type of remembrance, not remembrance writ large.

And that’s important because histories have lobbyists. Folks who are invested in telling more complete versions of U.S. history are gaining traction in their efforts. Those who have been lobbying for the histories that have dominated textbooks and curriculum for decades are understandably upset about that because those histories have benefited them. The United Daughters of the Confederacy implanted all these weapons in curriculum around the South. The same way that I grew up believing that North Carolina was the best place in the world, my high school social studies teacher talked about the “War of Northern Aggression.”

One of the things that was so striking about your protest was the way that you drew on historic symbols to highlight the raw politics of the present. It was just so well thought through to talk back to how others are using history.

I appreciate it. We thought a lot about that. That element of understanding that a noose is also a threat. It can also be a very powerful and violent symbol not even around someone’s neck, just hanging around a tree or on somebody’s door. Similarly, the Confederate statue is a threat. Some folks view this statue as an icon. This iconography is very, very different from how a lot of other folks see it.

Right. One of the ways that Italian Americans push back against Columbus statues is, “This doesn’t represent me.” But that doesn’t embrace the history that the statue does represent. It doesn’t work to counter it or to bring the full picture into the public consciousness.

One last question, what do you think our public history should look like and how should we get there?

The book that I was reading about Confederate monuments, it talks about how ladies’ historical societies, like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, went about the task of dedicating monuments for the purpose of valorizing Confederate soldiers, and not just those would have fallen in battle, but those who had returned. That’s quite a project, and it’s a project in patriarchy.

We do a lot of that, but particularly around a war. Either trying to valorize someone who is perceived as being the victor and it’s raising their stature. Or in the case of the “Lost Cause,” it’s doing so in a way that runs counter to reality.

I think that more useful public history challenges what we already believe and challenges the things that don’t even need to be stated because they are so widely believed.

Jerry J. Wilson is an educator, researcher, and advocate based in North Carolina who is committed to making learning environments productive and welcoming for all students. You can learn more about his work through his website.