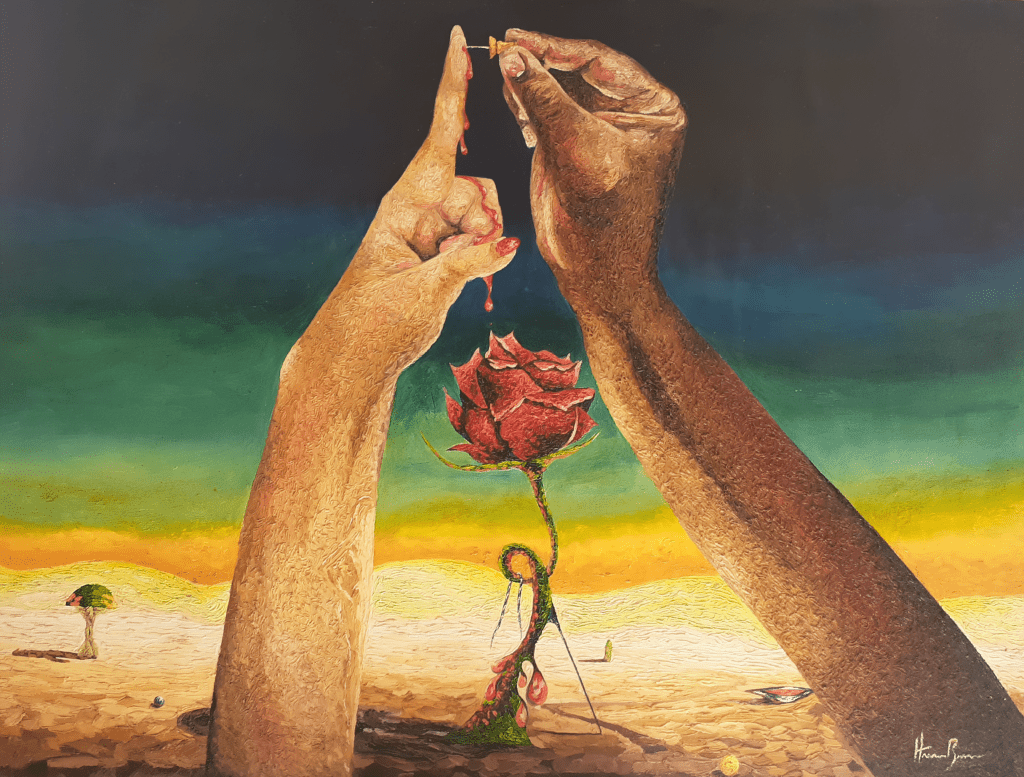

Artist: Hector Reynoso, Dominican Republic, Instagram: @ArtReynoso

by Pilar Hernandez

Growing up, when I would argue with my father about something I found unfair, I would yell “But this is AMERICA!” To which he would retort “not in this house, this is Cuba!”. Neither of my parents are from Cuba nor have ever visited but in our three generational, multi-ethnic household of new American immigrants, Cuba, held the exile of freedom in our imagination.

It was an absurd parenting tactic for a Central American man raising an American born teenage daughter in Rhode Island to employ, or so I thought at the time. Now, looking back I realize Cuba was the perfect example to use when trying to reason with a privileged, educated and passionate Latina, un-ironically wearing a Che Guevara t-shirt and crying out for rights and freedoms that were alien to him, down to his bones, no matter where those bones happen to be physically manifested.

So much like the experience of others in diaspora we live here and there, in minds mostly and bodies for some, but only if their human rights are recognized, therefore allowing them to travel freely. For those like my father who can never return home, not even in his mind and claims to never to want to, America had to become the outside, and left with no other option of what an inside could ever be. Cuba as other, was the authority and gate keeper of traditions traded too easily for assimilation in his mind.

In his imagination my father sought a staging ground for a lifetime of hard American questions, but he kept them locked up inside, disappeared into the Guantanamo of his full potential realized because the only other option was the possibility of something much worse.

As Cuba, in his house he had control, there was no debate, there was no thought, just obedience, which included compulsory devotion to and an overly inflated valuation of American education. The irony of which led to not only one but all five of his overly educated American born children to slowly pull away at the facade of dictatorship to find, just a man, trying his best to build a future with no guidance from a past, a legacy torn from him by civil war, a childhood unfinished, a father opening his borders just enough to let you see he is not crying.

“Why are you crying? He would often ask me, and before I could respond he would say “You were born in America!” As if my pursuit of happiness granted to me by the U.S. Bill of Rights somehow negated my need to process sadness. In my sharp, overly articulated English I would say “this is America?” and smugly in my fathers own tongue “¿Y que de Cuba?.

But like the imaginary Cuba of my father’s, the reality of the American dream was surreal and just as maddening. This was still no excuse to cry. So looking at my dad I learned if he could not cry then he would laugh, and that is how he survived the coup d’etat of his children, one by one asserting their authority over the other in the name of survival, growth, and progress, replaced by the next and the next, this time a bloodless revolution, but yet still far from painless.

With humor it was a becoming an American experience for him full of joy, excitement, terror, and most importantly guided by a love that learned to become patient and comfortable with being puzzled. As an educator I believe this is a great quality to cultivate for it encourages sincere inquiry which is my most treasured gift inherited from my father, former dictator now reformed and known as grandpa.

Today, I have two nieces, pandemic babies under two years old and already smart and demanding to be heard, as their constitutional right and biological human function guarantee them. They are grasping at the language of their lives to tell a story and I can’t wait to hear what they will say.

I wonder what questions they will ask of the world, what authority they will challenge, what incredible choices they will make as Americans born with the privilege of a knowable past, and the opportunity to live the future’s history in the present. But I know it won’t be easy for them, like it wasn’t easy for me, split between multiple worlds and cultures, each generation more divided getting further from our ancestors who we forgot how to speak with. I know it is my responsibility to share a usable past with my kin but I must admit I fear getting it wrong.

Looking back at the mistakes I made in my own becoming an American experience, I wanted to fault my mother for all the things she said and didn’t say to me during my most formative years. Her becoming American story differed from my father’s in several ways. Hailing from the land of Hispaniola she was raised on the fairy tales of Christopher Columbus, and just like many other Americans got to university to have her childhood innocence destroyed by the cold hard historical facts of genocide. Despite this awakening to the cruelty of exploration my mother was optimistic, brave, and privileged enough to move about the world much like the famed navigator. Unlike my father she came to the United States by choice on a plane and a dream, able to come and go as she pleased. A fair-weather mother, she moved like the seasons in and out of my life, and even in my knowing of her inevitable return, her departure left me gutted and longing for the warmth of her sun in the light deprived New England winters.

As a child I found this unstoppable movement distressing, it wasn’t until I returned to her country at the age of thirty-three that I could understand my mothers longing for her homeland. It wasn’t until my tired American bones reached that island as an adult that I could breathe and see her in her full humanity. I was not able to understand how a mother could leave her kids but now I can not understand how immigrants leave their souls behind like specs of coffee grounds at the bottom of cups, sat forgotten on sunset lit patios. The patios where communities would once gather now lay as empty as her dreams, serving as a mausoleum marking “here laughter and vitality once lived”. I don’t know how that is grieved. Even when you are able to return “home” it is just a short reprieve from that known death in the name of citizenship and assimilation. I don’t know who had it worse: my dad with no speakable past or my mom with a past that would not stop haunting her, leaving her restless and resentful for surviving it’s constant loss.

Still when my mom was present she would tell me about myself, that I was not white and I was not black, I was Dominican. That all Dominicans were black behind their ears, meaning even if you could not see it, we were mixed. This made sense even as I looked at her fair skin, thin long nose and at my grandmother with her gray eyes and 4B hair.

I always thought it was funny when people would be shocked to learn that my mother was Dominican and she would lean in and say “actually, I am Haitian” just to bring the point of race to the limits of its own absurdity. She is not unscathed, however, from the horrors of racism; both as victim and perpetrator, but she like I has this gift and curse of ambiguity.

She, like I, can frustrate the gaze, you are not sure how to insult us, and that always drives the bigot mad. Still this gift and curse of being unknowable lends itself to seeing ourselves in the other quite easily. We can see how we are similar to those we would normally have no way of empathizing with. We can also lose ourselves just as easily.

Growing up in a predominately Italian American neighborhood my mom would always tell me the “white” kids were not better than me and I was not better than them, and that we had more similarities in common than difference. I admit, I felt this to be profoundly true amongst schoolmates that were Italian American over those who were not.

My mom told me “Dominicans and Italians talk the same, loud, love the same, passionately, and eat the same, family style”. My high school best friend and I would commiserate on this topic together when discussing how “other” families were weird about dinner time and food, how their parents and homes were dull and dead compared to our homes, and that even in the chaos, it was full of people, laughter and noise that made you know you were alive.

I came to learn that this was the concept of campanilismo, which doesn’t have a specific English translation, but refers to the community which was formed by all of those within earshot of the church bell tower in an Italian village. In the Dominican Republic we call strangers vecino or neighbor and consider our neighbors to be family. My grandma was known as mama by all of those in her barrio who came to depend on her as a mother, healer, and provider of ancestral wisdom. My grandfather, who they called papa, would not allow his family to sit down to eat dinner until he announced to the neighborhood that the food was ready. This was to ensure that food was evenly divided to all of those without before they enjoyed what little they were blessed to have. The idea of having to leave someone’s home because it was dinner time was so foreign and offensive to me and my best American friend. In this shared cultural norm we could see each other but beyond all the similarities we could find, the search for understanding would be obscured in our inability to look in the eye our respective otherness.

When I would tell my friend she was not “white”, she was Italian she would tell me I am not black I am a “white” Dominican. This is a sentiment I would hear over and over again with my Italian American friends. I resented being called “white” not because I wasn’t, but because I knew deep down I could never really be, no matter how hard I did try. Before they brought me home their parents would hear the word Dominican and say “Oh, and is she BLACK?”. I feel guilty for being relieved when they would say “no, she is like us”, and shame in knowing that I never would be like them and never wanted to be but that I had to play along. I didn’t realize the entire time I was making choices or that I had choices. When my whole world is all I knew, I didn’t know how to look beyond myself and towards what I did not yet know. I had no way of imagining a world that was different then the one that was given to me. Despite my escape from the imaginary Cuba of my father’s and all my education and willfulness, I was ignorant and imprisoned by my own lack of imagination.

In the end that friendship took too long to die but when it did I was free to look honestly at myself and the ways in which I forsook my roots and the color behind my ears to maintain the perks of “whiteness”. As the first American born generation of my family, it was easy to challenge my dad’s authority as a myth but it was painful to let go of my mom’s fantasy of commonality. There are always limits and borders when it comes to “whiteness” no matter how close you get to stand next to its brightness, if you are not careful you will end up burned or worse, fully consumed and lost to the all destroying power of its own mythical creation.

I vividly remember my first sunburn that turned my skin red and made it peel instead of turning to black splotches that would always agitate my Guatemalan grandmother because it reminded her that I was indeed a different color behind my ears after all. I was twenty-one years old and I recall fearing the loss of melanin, youth, identity and connection to my skin and culture. I knew a lack of sun would not make me “white”, it would just leave me a cold hollow shell unknowable to my own community and yet still inaccessible to others.

With all my freedom of speech, still, I never said anything in any language. My tongue had grown tired and twisted, heavy in my mouth contorting itself to speak perfect English unblemished by a Rhode Island accent and forgetful of my first language, Spanish. I wanted so badly to just be understood that I never took the time to understand myself or my family or my heritage. Instead I wanted to see the world and speak Russian and Chinese and I did. I wanted to change the world, make history beyond my ancestors’ wildest dreams, but all I did was to explore the limits of my own privilege in “white” skin and my insatiable first world hunger for something that couldn’t be bought or consumed.

When I got my first passport as a child before visiting the Dominican Republic for a wedding, my mother held the little blue book in both her hands as she carefully placed it in mine and said “this is the most powerful thing you will ever hold”. I thought I held in my hands a tangible freedom, a birth right to devour the whole world, I did not realize that it was just another weapon of imperialism. Like a good American I gorged myself on travel without the thought of inviting others to eat at my table.

I would come and go as I pleased, leaving in my wake seasons of sadness in the cities, lovers and friends I would acquire during my visits, never feeling guilty because I called it adventure. Today I realize the value of community, the importance of being truly present and aware of those around me. I no longer feel like everything and everyone is happening to just me, I am also happening to other people.

The COVID-19 pandemic grounded me not only physically but mentally and spiritually, forcing me to look at myself and admit that I was playing games with real lives and that no amount of romantic myth making can bring the dead back to life. Nothing I say can justify my greediness to capture the whole globe in my grasping grubby little hands. When it felt like the world was ending my siblings gifted me hope in the possibility of a new one through the birth of their children. It is because of them that today I seek to understand more than to be understood, to love, more than to be loved, for I now understand it is in the giving of these things freely that we receive community and it is in dying and being remembered by those we touch that we receive eternal life.

I want to demonstrate by example this new understanding of freedom with the next generation of my American family in hopes of sparing them at least some of the pain wrought from the myth of individualism. For I can still hear the church bells ring and I am able to decide again every day anew to break down the borders that keep me from the world and the world from me. Armed with faith, I now wander the globe using the only true compass humanity has, imagination, in search for something better and bigger than myself.

About the author: Pilar Hernandez is just a guy from Rhode Island, who finds humor in language so she attempts to speak several of them. As a self identified AFAB individual, using she/her pronouns, she is committed to being a life-long learner and conspirator of love. Pilar’s career in international education and passion for the arts inspire her to write in pursuit of truths and beauty that are both specific and universal. She hopes to continue writing and contributing to a theory of education for the recovery of the public world and collective joy, and to one day pay back her loans from Suffolk University, and New York University, Tisch School of the Arts, but has absolutely no shame of dying in debt in the pursuit of knowledge.