An interview with Potito Paccione

by Ross Caputi

December 5, 2021 | Potenza, Italy

Italy is a country of infinite complexity; ethnic, racial, and linguistic diversity; regional particularities and cultural heterogeneity. Yet, in American society, and even within our Italian-American communities, Italy and the Italians are ever more reduced to clichés and stereotypes. Yes, Italians eat pasta. They gesticulate when they talk. And the mafia does exist. These tropes circulate ad nauseam in cinema. They are the stuff of dad jokes whenever Italy comes up in conversation at family dinners. And yet we cling to them because they are the last crumbs of our impoverished sense of heritage in Italo-America.

I grew up, like so many of us, treating these clichés like communion. We all bought cannoli at the Saint Anthony festival, because that’s what you did. We put tomato sauce on everything, because that was the essence (or so we thought) of Italian cuisine. Everyone in town had a tattoo of an Italian flag, but no real understanding of where exactly their family came from. And then there were all the feel-good little things: Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro collaborations. Pizzelle wafers on Christmas. Statues of the Madonna in the front lawn. And the little, dome-shaped white frosted cookies with rainbow sprinkles. We partook in these old chestnuts of italianness in order to feel close to our roots, but the Italy of our grandparents was always distant and indistinct.

It was on a total whim during a backpacking trip in Europe that I decided to visit my great grandfather’s birthplace, Grumento Nova, a small village deep in the southern Apennine Mountains. After three hours on a rickety train from Naples to Potenza, the regional capital of Basilicata, and then two hours by bus over winding mountain roads, I arrived in a hilltop village overlooking the Agri Valley. But for all its geographical ruggedness and remoteness, what felt most exotic to about Grumento Nova me was my unfamiliarity with the culture, the cuisine, and the language. Rich in particularity and history, Grumento Nova has it’s own language, it has a cuisine that doesn’t smother everything in tomato sauce, and it has its own set norms and traditions. Somehow, my family had lost all of that.

My academic work has since focused on shedding the clichès of my Italian-American upbringing and rediscovering the particularities of my roots. In the course of my own search for specificity and uniqueness, I have stumbled across dozens of little-know treasures of Italian history and culture. Beyond Dante, there are dozens of languages and local literatures that all have their own geniuses and charms. Beyond the history of Rome and the renaissance, there are micro-histories and local histories of endless abundance and of enormous value. And they reveal a world of perspectives and experiences left out of the history books, of lived realities both too ordinary and too tragic to make it onto a postcard, of modern experiences eclipsed by the world’s fascination with Italy’s past.

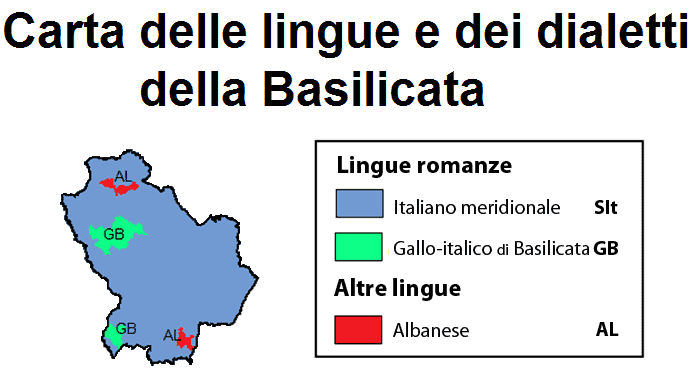

Today I bring you one—the phenomenon of Gallo-Italic dialects in southern Italy. Though widely spoken in northwest Italy, there are Gallo-Italic islands of mysterious origins in Sicily and Basilicata. Much has been written on the characteristics of these dialects, the possible explanations for their survival in isolated communities in the south, and potential periods of migration that could have brought them there. But the dates remain vague (we’re talking about somewhere between the 12th and 13th century), and there are no definitive historical documents attesting to the causes of these migrations.

However, in the absence of definitive historical documents, one graduate student from the Università degli Studi della Basilicata is using linguistic data to shed some light on the mystery. Potito Paccione was born and raised in Potenza, one of the region’s Gallo-Italic speaking communities. Potito is doing his dissertation research on the diffusion of Gallo-Italic dialects and their relative endangerment. And he has an interesting methodology that might be able to tell us more about where Basilicata’s Gallo-Italic dialects came from: Potito goes looking around in the graveyards of small villages.

In the following interview, I ask Potito about his research, the mystery surrounding the Italo-Gallic dialects of Basilicata, and his unique research methodology.

RC: So what exactly are these Gallo-Italic dialects in Basilicata?

PP: In Basilicata the Gallo-Italic dialects are concentrated in two main areas: There is a cluster of communities in the Policastro area—Nemoli, Trecchina, Rivello, San Costantino—and another around Potenza, including Tito, Pignola, Picerno, Pietragalla, and Genzano di Lucania. The most salient features of these dialects are common in all Gallo-Italic dialects, even those in the north, and they also share features with most southern dialects, because of course these communities have been here in the south now for seven or eight centuries.

The most marked feature of these dialects is definitely lenition, consisting of a systematic weakening and voicing of certain intervocalic consonants. So for example, in standard Italian and in most Southern dialects we might find the voiceless stop /t/ where the Gallo-Italic equivalent would have the voiced fricative /ð/. Consider the word for “you have (plural)”, which in standard Italian is avete and in many southern dialects is avitə, the Gallo-Italic form is aviðə. And we see a similar pattern with the consonants /g/ and /p/ as well. The /g/ in the standard Italian form for “to play”, giocare, is jucà in many southern varieties, but giuɣà in Gallo-Italic varieties, with the /g/ becoming a voiced velar fricative. Similarly, the /p/ in the standard Italian word for “onion”, cipolla, while present in the common southern form cipuddə, becomes cəvoddə in Gallo-Italic varieties.

RC: What is the main argument of your dissertation?

PP: First and foremost, I’m analyzing all of the Gallo-Italic dialects of Basilicata, including the well-known cases in the area around Potenza, but also cases where there have been questions about their Gallo-Italicness and their surrounding communities. The idea is to look at the diffusion of Gallo-Italic features, which might have been lost in some communities or might be present in others due to linguistic contact. The most marked features of these Gallo-Italic dialects are also the easiest to lose, precisely because the stand out, both in contrast to standard Italian and in contrast to other southern dialects. Gallo-Italic dialects are doubly stigmatized, so it is possible that a community of speakers my not present Gallo-Italic features today, but that doesn’t necessarily mean their community never did.

Take for example Potenza. If you speak with a 70 or 80-year-old, you’ll here this phenomenon of lenition in their speech across the board. But if you speak with someone my age, it’s possible you won’t hear it at all. So it’s very possible that a dialect that doesn’t present this phenomenon today did at an earlier point in time. That’s why there’s the need for a comparative analysis of this kind.

RC: How did you become interested in these Gallo-Italic dialects?

PP: Well, half of my family is from Potenza. You could say my life was split between Potenza and Trivigno, which is 10 minutes from Potenza by car. So growing up my parents spoke two dialects in the house and I was always aware of the huge differences between them and of the really archaic features of Potenza’s dialect, which I knew through my grandmother. Of course I couldn’t articulate what those differences were, but I was certainly aware on some level of the features I already mentioned, of this phenomenon of lenition. It was only later when I went on to college and began to study dialectology that I gained the vocabulary to be able to explain the differences that I was already tacitly aware of between the dialects that I grew up with.

Anyhow, I became interested in these Gallo-Italic dialects and their history, and also in the grammars of Neapolitan dialects. It’s something that I’ve pursued to this day, and now I’m working on a doctorate in the subject and I’m constantly trying to dig deeper into it. But I was always interested in dialects, even as a boy. It’s only in recent years that I’ve been able to think about and research them in a scientific way.

It’s also very personal for me. The dialects that I speak, the full range of Italian dialects, and dialects in general are sort of a Giano Bifronte for me, both personally and in terms of their scientific importance. You could say that I my interest in dialects started as a labor of love. But of course I speak Potenza’s dialect, so I’m also connected to the field of dialectology in a very real way.

RC: Can you tell us a little bit about the history of these Gallo-Italic dialects? Where do they come from? And how did they end up here in Basilicata?

PP: It’s very difficult to get into specifics, where they come from or how they got here, because all of this is still laking proof. All of the studies over the last 200 years have never been able to reach any sort of consensus and there is still very little that’s certain. They’ve never been able to pinpoint an exact area where they came from or a specific period in which these migrations occurred. There just aren’t any documents that can serve as hard proof.

Without a doubt there are northern Italian dialects with very similar features, so we know that is the vague area of origins. More specifically, we’re probably talking about Liguria and Piedmont. The majority of studies seem to suggest that Liguria is the most likely point of origin. But I think a polygenetic explanation is also possible. So it could be the case that we’re talking about a migration from a general area, rather than a specific location. And this is a hypothesis that the International Center for Dialectology here at the University of Basilicata has been trying to support with linguistic data for some time now. In addition to the hypothesis there was a migration coming from Sicily, as well, because the Gallo-Italic dialects of Basilicata also show features of Sicilian, especially the vowel systems of the Policastro dialects, but also in the dialects around Potenza.

So, my hypothesis is that there was a migration from the Liguria and Piedmont area to Sicily, and then from Sicily to Basilicata. And this doesn’t exclude the possibility of a simultaneous migration from the north directly to Basilicata. So, it could also be a polygenetic migration in this sense. And this may have taken place at a discrete point in the 12th and 13th century, or it could have been a phenomenon continuing through this period. It seems near impossible to identify a specific date, so we may be looking at a decade, or even 100 years, when all of this took place. It could have been caused by an event, like a war or some sort of catastrophe, that pushed these people to migrate south, or perhaps there were religious motives also. It’s not uncommon for migrations to be polygenetic in this sense. If you look at the patterns of migration to the Americas, for example, you see migrations and chain migrations continuing for hundreds of years from the 16th century onwards.

RC: Do you have any thoughts about what sort of events might have caused these migrations?

PP: One possibility that seems to support the linguistic data is the war between the House of Suevi and the House of Anjou for the Neapolitan throne. Once Charles of Anjou took power in 1266 a.d., they completely destroyed any city that was loyal to the Suevi, raised them to the ground, and then repopulated them with loyalists to the House of Anjou. This much we know, so it could explain migrations coming from areas already under the dominion of Anjou in Sicily to newly conquered areas in Basilicata. But this is still just a hypothesis and it needs to be backed up with evidence.

RC: So, when you go looking around in graveyards, what exactly are you looking for?

PC: It’s onomastic research, I’m looking for the diffusion of surnames. It’s a more recent addition to my research, but basically I’m looking to understand what sorts of patterns of migration occurred between small villages. Take for example Potenza, where the nine original surnames actually come from Avigliano. So naturally in the cemeteries of Potenza, you see a lot of Aviglianese surnames. You can also see generational differences in the origins of many surnames. If you understand a bit about a town’s history and its relationship with neighboring towns, maybe even its relationship with towns further away, it can be a way of tracking patterns of migration from town to town. For me it’s interesting to see common clusters of surnames between the Policastro region and the Gallo-Italic speaking communities around Potenza. So, the onomastic data is just another layer, in addition to the linguistic data, to support a hypothesized exchange between these areas at some point in history.