By Chris Lombardi

The year before Richard Nixon’s re-election, I’d just turned ten years old, and often wore my “President Nixon” button to school. My friend Gina and I once chanted a made-up jingle for Nixon, in her Long Island bedroom: “Hey hey, hear all about it/McGovern got elected and there’s no doubt about it/Two bucks for pizza and a tax on ice/And we don’t think that’s very nice.” At a time when a slice of pizza cost thirty-five cents, the prospect of a two-dollar slice was unthinkable. As now, inflation was an election bugaboo, and our 10-year-olds’ prediction of McGovern’s dystopia revolved around making things expensive.

We made our parents laugh, which was kind of the point — to laugh about the unthinkable happening, that some guy I’d barely heard of would replace the only president I’d ever known. Not to re-elect him was downright dangerous, our parents said, and we believed with all our hearts. Gina and I chanted with so much joy; I remember almost shouting, in hearing range of our parents. All of the latter were staunch Republicans, like many Italian-Americans in the environs of New York City.

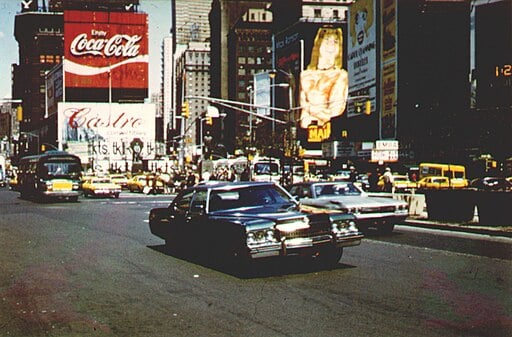

Long past the years of lefty “Harlem Italians” like Victor Marcantonio or Fiorello La Guardia, these Italian families were both solidly Republican and explicitly right wing, against liberal social welfare policies and insisting the city needed to concentrate on fighting “crime.” They also filled the ranks at the NYPD, along with their same-generation-fellow-immigrants — the Irish-Americans. Many, like my father and Gina’s, were also explicit racists. They liberally used as racial slurs the word “mulignam” (eggplant) and its abbreviation “moolie.” They’d grown up together in the South Bronx in the 1940s, just as generations of African American families arrived as part of the Second Great Migration, and their hostility toward the latter was undisguised, though by the time I could hear it they’d already learned that explicit racism was unacceptable and even the m-word borderline. Thus the emphasis on welfare spending and inflation, a thesis that “liberal” policies was raising the cost of living for hard-working Americans. “Two-dollar pizza and a tax on ice” was thus a poetic summation of the case against Black New Yorkers born in the South. Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” is famous for how it turned formerly Democratic counties in the South into fierce Republicans, exploiting voters’ racial backlash against the party that had passed the Civil Rights Act. But those same notes worked with Northern whites fearful of losing status to newly empowered Blacks.

NYC Italian Americans were also bullish on Columbus. Cristoforo Colombo, the guy who “discovered America.” Us second-generation immigrants knew we were American — and excited to learn that “Christopher Columbus” was actually Italian. Italian American, just like us. My second-grade teacher, one October day, challenged us to sing about Columbus. She played a tune, “Spanish Flea” by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, and gave us the first line: A boy from sunny Italy… I was the one who supplied the rest, right up to the refrain: He claimed it in the name of, in the name of, in the name of Spaaaaain! In the name of Spain!

In the years since, I often have said that I peaked at age nine, since I wrote the class Columbus Day play. I certainly never stopped to think how colonialist that school play was, not least with its faux-Mexican tune. And god knows we never thought about who else was inhabiting the land Colombo claimed, let alone about how it was all superpowered by the Doctrine of Discovery that his Church and mine had issued, saying that everything Catholic invaders came across was theirs. Until relatively recently, that dumb song was what came to my mind when anyone mentioned Columbus Day — that, and New York City’s bodacious Columbus Day parade, one of those days when my family went “downtown” to Manhattan.

By the time I was singing Herb Alpert songs about him, we’d learned to justify our love for Columbus by calling it anti-discrimination. For years we’d learned about the past, when “No Italians Need Apply” signs and ads limited our ancestors’ job options, when hatred for “guineas” and “wops” (us) was widespread. By celebrating Cristoforo Colombo, the guy “from sunny Italy” who “discovered America,” we could help abate such discrimination now. By 1972, the year I wore the Nixon pin and chanted about inflation, there was a new movie out which stereotyped us. We loved the famiglia stories in The Godfather, so we marched on Columbus Day to prove we weren’t gangsters — not violent like the Blacks and Puerto Ricans we’d learned to fear.

What do I remember about those parades? Those memories are not easy to find — or, frankly, any real memories of my childhood. When asked I usually mention the 1965 blackout, perhaps my first memory, my parents playing cards in the dark in our house on Coddington Avenue; I don’t talk about all the yelling. My late father, now so beloved I dedicated my first book to him, was someone I feared then, a man both morbidly obese and full of rage. His shouts, his threats threw a fog over my memories, the dissociation of someone unclear whether she was actually getting hit, but who took seriously his joking threat that “I could kill you and make someone just like you.” Any anger back I might have felt was subsumed in the fog.

I do think the whole matter made my dad’s racism land differently, and I couldn’t hate who he hated. Those “hippies,” the protesters against the cops, seemed at least interesting. All of which is my usual explanation for how this family, who were MAGA even before Trump, produced someone like me –– a writer who now tags myself an “aspiring anti-racist,” trying to find a useful way to confront my own whiteness and the harms associated with it.

I recognized Trump right away because in his effort to sound like The Godfather, he sounded like my dad. Or my youngest brother, my baby brother, who congratulated me in 2008 on the election of President Barack Obama, my “HNIC” (which I refuse to transcribe, but the N-word is what you think it is). Or the uncle, my mother’s baby brother, who stopped wearing Nike because he was offended by Colin Kaepernick. And to my eternal shame I said nothing, most of the time; I did recently offer to send my brother a copy of Nell Painter’s A History of White People and was told he would burn it if I did. I still went to Christmas dinner. That was our peace treaty.

The family consensus is that everything changed when I didn’t go to a Catholic high school but went instead to Hunter College High School, part of the liberal City University of New York establishment.

But while Hunter High was formative in my life, I think that change began far earlier; perhaps when I was 10 and hit by a car in my neighborhood, driven by the wastrel nephew of one of my Italian-American neighbors, and the first person I saw when I opened my eyes was a kind man with brown skin. I remember being surprised, as if I were learning something,

A year later, I was offered the chance to get out of my local school to a new middle school, one for “gifted and talented underprivileged children.” I knew I wasn’t the latter, in the house my grandfather built for us and the Cadillac in our garage that might’ve been a Corvette had my baby brother not come along. But the G&T tag made sense for the kid others called “Computer” and worse.

The “Kips Bay School of Arts and Sciences.” It sounds like a kids’ movie, an After-School Special, especially when you mention that the school held its classes in a Boys and Girls Club in the South Bronx. One that had relocated from the actual Kips Bay, snuggled up against the East River right by Gramercy Park, but kept its name a few miles away in working-class Castle Hill, a few subway stops away from my own.

It was the late spring of 1973 when my fifth-grade teacher told us there was a new school for gifted and underprivileged kids. The latter category barely applied to my all-white neighborhood school, but I jumped at the chance to try something new. It wasn’t as if I had any friends, the only currency relevant to tweens.

I didn’t think twice about the idea of being “bused” to my new school, a verb close to a curse in my house. For 1973 was the year headlines exploded about parental objections to “busing” — the practice of desegregating schools by transporting children out of their home communities on school buses. Unpopular with both Black families and whites like my parents, busing had been authorized in 1971 by the same Supreme Court that had decided Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, in response to a lawsuit that said that the court’s goal in Brown of integrated schools needed a little push, especially in the South. The 1971 order is most famous for putting 35,000 Southern children into school buses out of their neighborhoods, but also for the resistance of white parents, not only but most famously in Boston, all aghast at the idea of Black children being bused into their communities, let alone putting their kids on a bus out of their sight. In my parents’ Bronx (as in Trump’s Queens) the idea of court-ordered desegregation was evidence that they needed to either fight for their city or flee — the famous “white flight” that would ultimately drive two-thirds of white families to move to the suburbs.

By 1973, New York City schools were newly decentralized; a response to a protest movement led by Black families in Brownsville, Brooklyn, that had included a long, bitter teacher’s strike in 1968. As explained by education scholars from Derrick Bell to Diane Ravitch, author of The Great School Wars: New York City, 1805-1973, the movement — which erupted more than a decade after the Supreme Court ruling in Brown gestured toward justice in public schools — included civil rights icons Bayard Rustin and Stokely Carmichael. In 1969, the state legislature in Albany responded to all the fuss by putting the schools under the control of hundreds of Community School Boards, along the way establishing the position of Chancellor of Schools. For the latter, the state offered the job to everyone from Sargent Shriver to Ramsey Clark, before settling in 1970 on a Maine-born educator named Harvey Scribner, who’d successfully integrated Teaneck’s public schools. The following years were characterized by all sorts of innovation: open classrooms, Black and Chicano curricula, and the integration of visual and performing arts into all kinds of learning. In Brownsville, a campaign for resource equity became plans for the first all-Black school district, empowered to hire more Black teachers. That plan went nowhere and when Scribner resigned in June 1973, the spirit of innovation seemed to ebb. But some of the projects approved by Scribner went forward, including an unprecedented collaboration between Community School District 8 and the newish Boys and Girls Club at Castle Hill.

Thus in the fall of 1973, I walked along dark streets to get to my bus on time. That year, New York City schools stayed on Daylight Savings Time deep into the school year, because of what was called “the energy crisis” after the end of cheap oil from the Middle East. The bus taking me to my new school picked me up from my old one. Public School# 14, on Bruckner Boulevard in Pelham Bay, was a 10-minute walk from my house on its block of neat single-family homes mostly inhabited by Italian immigrant families. I walked past the pizzeria that sold slices to tweens like me, and the gas stations whose dogs haunted my nightmares, till I got to the slice of Bruckner Boulevard that held my elementary school.

The yellow school bus waited on the street beside the school, and it was usually near-empty, making me one of the first to get on. It took a while to get used to the fact that we were being taken not to a school building but a Boys and Girls Club, and that 70 percent of the school’s pupils were Black and Hispanic, quite a change from my elementary school where the only ethnic differences were whether you were Irish or Italian.

What do I remember from the Kips Bay School of Arts and Sciences? From that first week of school, I remember that when we were all told to stand in alphabetical order by last name, I refused to move at the demand of a slim Black girl whose last name began with N, who felt much taller than me but was also just another 11-year-old. I won’t move because mine begins with L, I told her and didn’t back down. I remember months later consoling that same girl, after someone broke her new Kool and the Gang album. I remember classes held on basketball courts, students clustered on the bleachers. I remember writing papers about endangered species, the osprey for a science class and the Osage tribe of Oklahoma for a social-studies class that focused on Native Americans. For the latter paper I kept thinking how the Osage were never mentioned in my dad’s favorite musical, “Oklahoma.” (At no point was the Discovery Doctrine mentioned.)

I also remember the school librarian who loaned me a book entitled Going to Jail, and that’s how I learned that the United States had political prisoners. I remember going to New Rochelle for a sleepover at my friend Maritza’s grandmother’s house, and wishing I knew enough Spanish to understand their TV shows. I remember the day I got beat up on the bus, by an Irish girl who said I was stuck-up because I’d never gravitated to the other white girls at the back of the bus.

I’ve often tagged September 1974 as Liberation Day for me, the day I landed at Hunter High’s 466 Lexington Avenue campus and felt for the first time like someone spoke my language. But 1974 is also popularly known as the year “the Sixties” turned super-toxic, the year the Bronx started burning as the city verged on bankruptcy. I think the real Liberation Day came a year earlier, when 11-year-old me walked to school in the dark toward something new. You could call it my own Doctrine of Discovery, yearning to dig up the truths behind the American Dream.

Chris Lombardi is a journalist, novelist and playwright, and a member of the Editorial Committee of Democratic Socialists of America. Her coverage of housing issues and prison issues earned her awards from the New York Press Association and a Community Leader Award from Housing Conservation Coordinators. Her 2020 New Press book I Ain’t Marching Anymore: Dissenters, Deserters, and Objectors to America’s Wars is a product of years working on war, peace and veterans’ issues. Her fiction has been shortlisted for the Pushcart Prize and the Bellwether Prize, and can be found in The Millions, Failbetter.com and assorted anthologies. Her journalism has appeared in The Nation, Waging Nonviolence.org, Guernica, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ABA Journal, and at WHYY.org.