The Shoebox Negatives: A Trove Rediscovered

by Joan Tortorici Ruppert

My dad died in 1964 when he was 43 and my mom was 38 years old. Over the decades that followed, my mom lived in apartments where space was limited and storage was highly prized. Only the most important objects survived brutal rounds of downsizing. That’s why I was baffled when, about 30 years ago, my mom reached into the closet of her studio apartment, took down a shoebox stuffed with hundreds of photo negatives and handed it to me. Everybody keeps photo albums. But negatives? “Your dad took these,” she explained. She told me he developed the film himself and that he had been an avid hobbyist.

What prompted this unexpected conversation was my mentioning that I was taking a darkroom class. Upon opening up the shoebox, I could see right away that the oversized single-frame negatives wouldn’t fit in the standard-issue 35mm strip holders used in my class. Still, I was excited to become the collection’s new caretaker. Some years later the box tumbled into a massive basement flood. Panicked, I dumped the negatives into a bucket with water and Photo-Flo and strung them back and forth between the walls of my house to dry. Many of the negatives’ corners still bear diagonal clothespin scars from that rescue mission.

The negatives went into a better box in a safer place, out of sight but not out of mind. I still didn’t know how to approach the project from a technical standpoint. But finally, just before the pandemic shutdowns, I was ready to figure it out.

Challenges and Discoveries

It didn’t take long to discover what would become my most daunting technical challenge: the negatives themselves. Nearly all were irregularly hand-cut individual frames. Many had severe curls, folds, waves, thumbtack holes and other physical flaws that defied all attempts at fitting them into standard holders or getting them to lay flat. As I dug deeper for solutions, I learned about fluid mounting: a pre-scanning process that sandwiches the negative between a mylar sheet, specially treated glass and a liquid. This was the key to taming my unruly negs and coaxing the best possible quality from the high-end flatbed scanner I’d found at a bargain price on eBay.

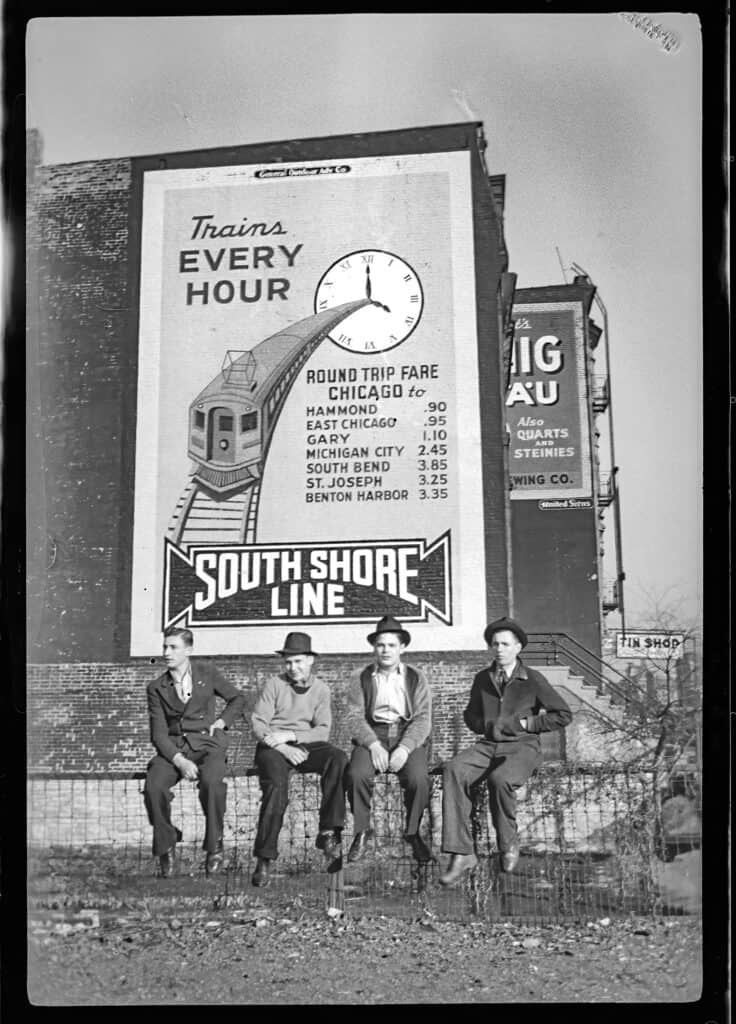

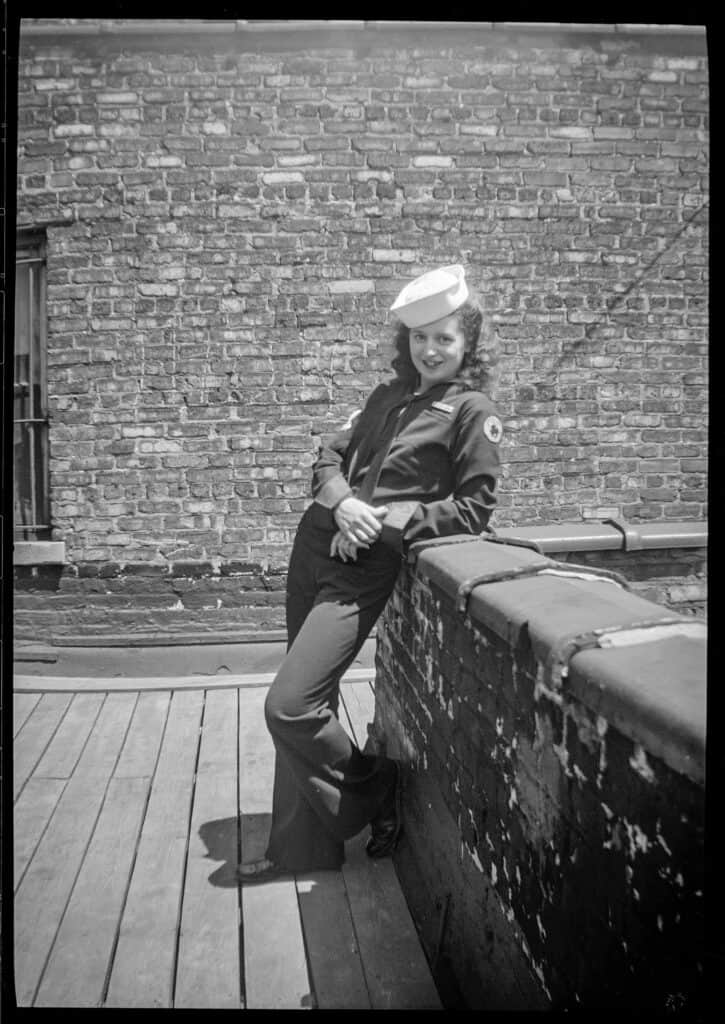

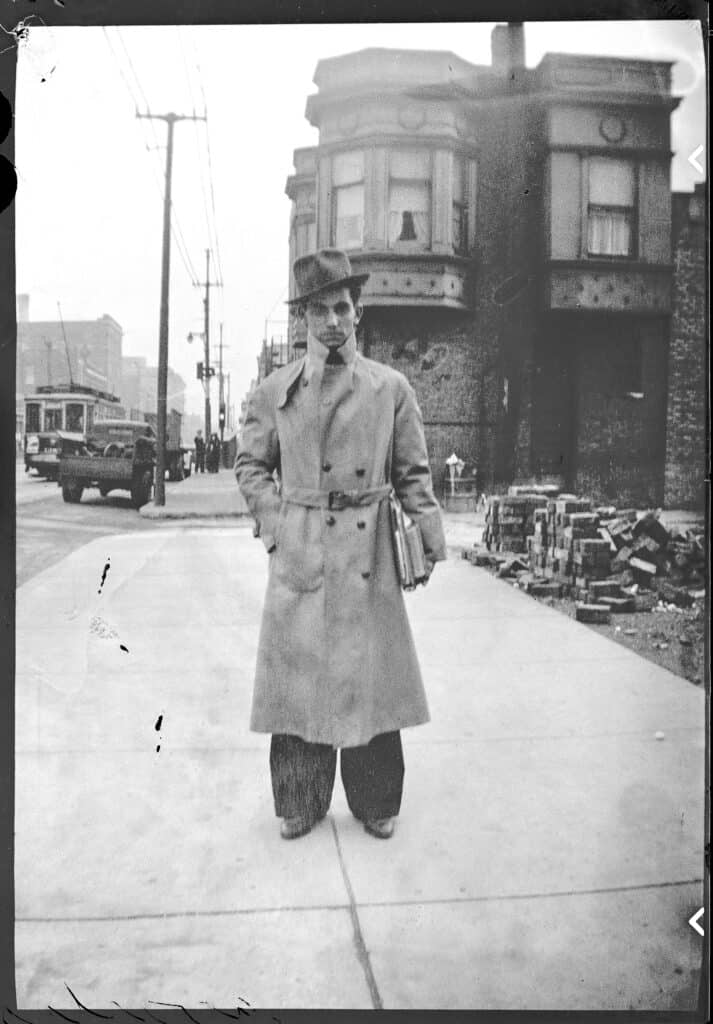

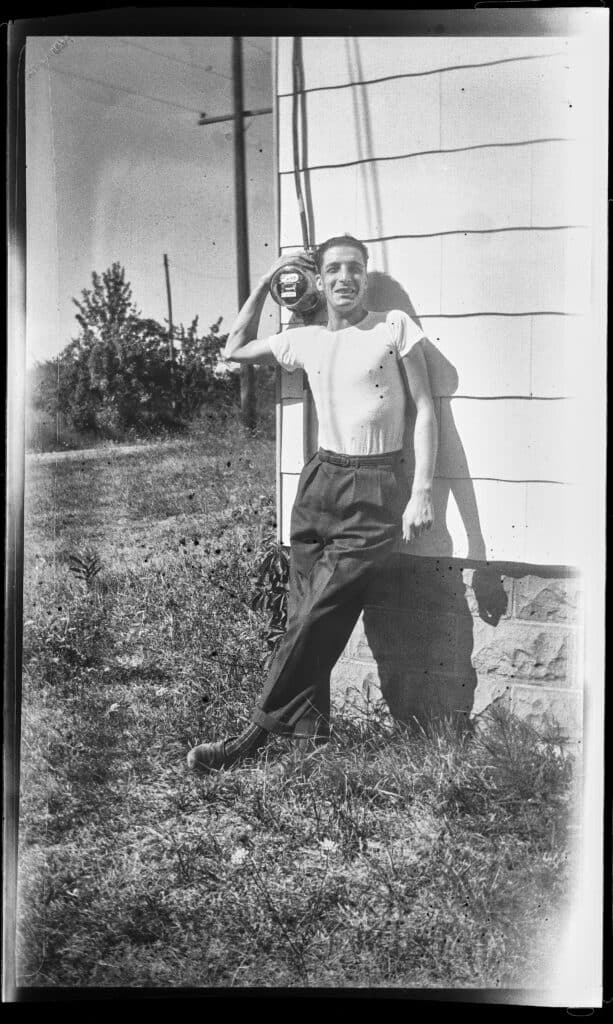

As I culled the negatives, I figured out that most were taken when my dad was quite young, not long after his high school graduation from Crane Technical High School in 1938. A lot of the images show guys doing guy stuff: climbing up on billboards, mugging for the camera, standing next to cool cars they likely didn’t own. There’s a lot of what feels like easy camaraderie in the scenes my dad captured, reflecting his life in a working-class Chicago neighborhood just before America’s entry into WWII and his joining the U.S. Navy where he served as a radioman on a minesweeper.

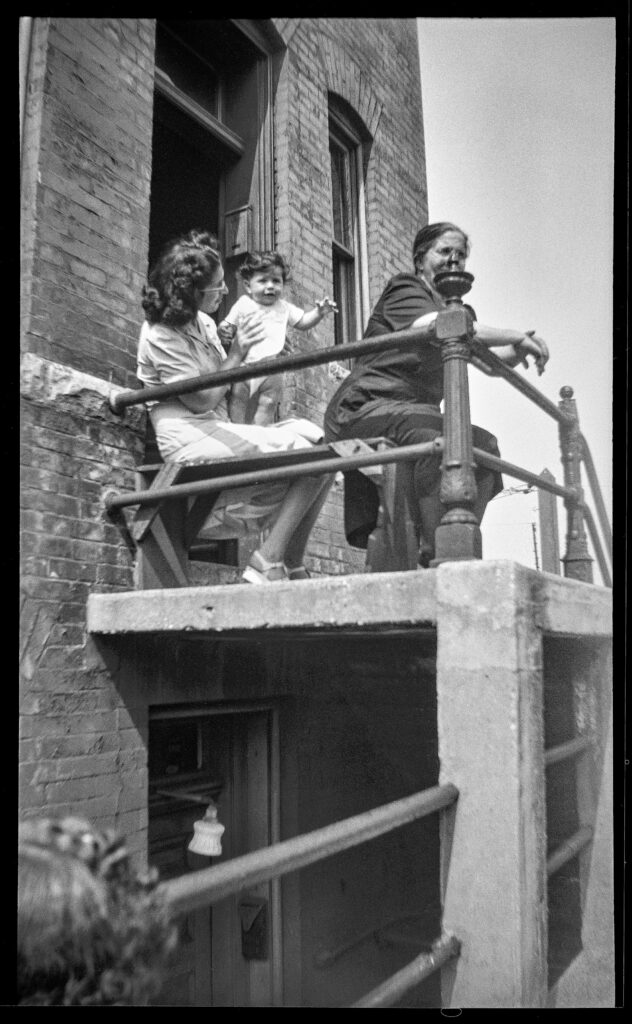

Months after I’d culled the collection, my sister discovered another batch of our dad’s negatives while cleaning out a storage room. This batch was smaller than the first, but the notable twist was that these were all taken after my dad’s 1945 return from the war. I’ll never know how or why the pre-war and post-war batches were separated. What’s clear, though, is a distinct lifestyle change. Instead of depicting a group of buddies making human pyramids at picnics and posing with girlfriends, the photos tell the story of marriage, babies, holidays at home, and a big move from a city apartment to a new house in a suburban wilderness.

Staying True

Almost none of the negatives in the collection have corresponding prints in our family’s photo albums. But there are a few, and their dimensions suggest they were contact prints. For that reason I committed to leaving the compositions as close to their original state as possible without cropping or straightening. If my dad didn’t have access to an enlarger, I wanted the finished images to stay true to his reality. Another decision was to keep fixes (for flaws like scratches and nicks) to a minimum. Each frame presented a unique set of challenges in terms of physical condition, exposure, and just about every other attribute. Some took hours to process while others took days.

Sharing

Once I had processed what I felt was the core of the collection, I tentatively shared a few images on my Facebook page. I didn’t expect much of a response from acquaintances with no connection to my dad. To my great surprise, the feedback was immediate and enthusiastic. That gave me the confidence to cast a wider net, and today The Shoebox Negatives have been seen in countries across the globe.

Learning to evaluate the images based on merit versus sentimentality isn’t easy for me. And to be honest, I’ll probably never be truly objective about any aspect of this project, although I’m getting better at it. The response from people outside my circle of family and friends continues to offer valuable insight into what works and why.

My original mission for The Shoebox Negatives was to figure out how to bring them to life. That’s a work in progress. In the meantime, the parallel goal is to have them seen. But at the heart of it, the best part of this project – and the part that really counts – has been discovering which tiny slices of my dad’s life he felt were important enough to capture on film, back when cameras weren’t in every pocket or purse. The shoebox became a window, and there’s still so much for me to see.