I had to wait five long years for Elena Ferrante’s next book after her last one, The Lost Daughter (2006). My Brilliant Friend, the first volume of what became the world famous quartet, came out in Italy toward the end of 2011. I had moved to San Francisco from Naples about two years earlier, and among my dearest belongings I had carried Ferrante’s books in my suitcases for fear of losing them in the shipment boxes that would join me later. My next visit to Italy was planned for the summer, and I couldn’t wait any further to read her new book. I called a friend in Italy and asked him to mail me the book as soon as it hit the bookstores. A week later, winning the battle against the Italian mailing system, my object of desire made it to my door in San Francisco.

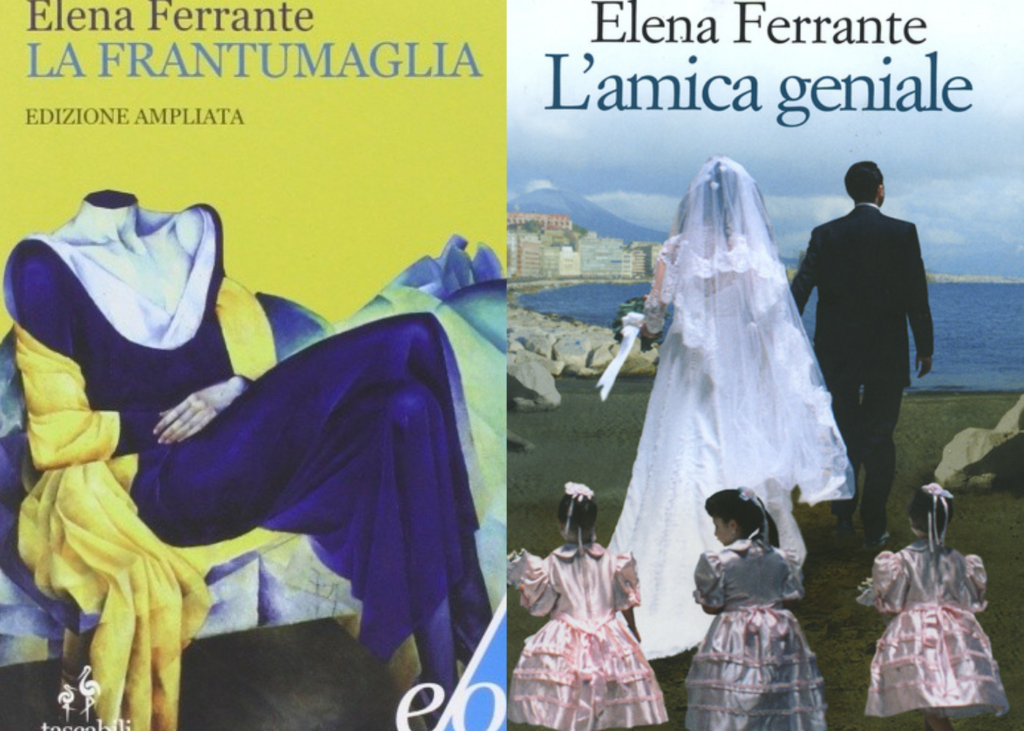

The cover of My Brilliant Friend surprised me. Where were the beheaded women of the previous novels? Or the women laid bare before themselves and before the reader’s eyes? And if not another beheaded woman, where was that disquieting imagination that already oozed from the book cover? Here was a woman in a white wedding dress, walking on Mergellina’s beach with her groom, and Mount Vesuvius overlooking Naples’ bay in the background. This quasi-postcard view of the city—a view that I had watched and loved for most of my life—was too comforting, too subdued for the sense of uneasiness that always assaulted me before turning the first page of any of her books. What kind of story was hiding beneath that plain cover? I was about to find out. I turned the phone and computer off, and checked that I had enough food in the house. Given the over 300 pages, I was prepared for at least a two-or three-day immersion into Ferrante’s writing, with no interruption.

And here I am, thirty pages in, I sit still but my muscles are contracting and twitching, my jaws tightening anticipating the next line, plus I have this sinking feeling in my stomach. I catch a few words on the next page, and “Basta, it’s enough,” I throw the book against the wall. I know where this story is heading. Then I glance at the deceitful cover and pick the book up. I open it at the page where I stopped, and reread the last lines: little Lila is lying on the sidewalk with a gash in her forehead after having thrown rocks in a fight with some boys. Blood is leaping off the page.

I shut the book, and with no hesitation I put the long awaited volume away. I did not open it again until four years later.

I left two nine-year-old girls, Elena and Lila, wandering about their ‘hood, the Rione Luzzatti in Naples’ eastern periphery, the same rione where I paid frequent visits to my aunt in my childhood years; a place, as Elena says, in which “the light on the stones and on the buildings could not be trusted, nor the people inside and outside their houses—”; a place like any other marginal neighborhood of my city. The cellar, the shadowy caverns, the dusty courtyard of the first thirty pages to which the girls “attributed everything that frightened them,” were not fictional places to me. I had been there, I had played in that courtyard, I had feared the cellar, the attic, the elevator, the stairs; and every terror that in Elena’s and Lila’s story didn’t match mine, I had either witnessed or escaped.

In a half hour, the book on my lap turned into a black hole that, without warning, dragged my entire self back into the universe from which I had slipped away. Elena the writer, Elena the narrator, used precise, unequivocal words to name, distill, and unearth all that was concealed deep inside me. It was as if I had been led into a dark room to watch hundreds of old photos of me and people I knew develop before my eyes, and with a sharpness that left no room for doubt in comparison to the more benevolent blur of my cautious memory.

I had been Elena without Lila. My own brilliant friend was another Elena. We were a blend of the two mixed together, always alternating between disobedience and submission, boldness and fear. My sister, my girlfriends, and I were mostly Elenas afraid of Lilas, and yet, we were fascinated by Lilas. They were all around us. They intimidated us more than boys because if boys were a world apart from us, these girls lived in our world, and it was mostly with them that we had to measure up: we expected them to behave like us, speak like us, look like us: a bunch of eight-year-olds just wanting to play free; instead they wore lipstick and heels like their mothers, and cursed and hit like their fathers and brothers. My Lilas had no fancy nicknames, they were called Anna, Maria, Titina; they never checked out books at the library, they ditched school, and never taught themselves to speak or write proper Italian, let alone Latin and Greek.

We, the girls in my building and I— the girls half-Lila, half-Elena— threw things too, but, unlike Lila, we were cowards. We threw things from balconies and windows so that we could hide: bottle caps, clothespins, dirty paper and rags, and we spat over people’s heads. We hoped to hurt someone but feared hurting them for real. We pulled each other’s hair, we scratched, slapped, hit. We often returned home with bleeding noses, bruises, and aching limbs. Once, my sister pulled a classmate’s hair so hard that a sparse tuft of the girl’s bangs came whole into my sister’s hand, then it was theatrically tossed into a trash can. Another time, a girl extinguished a lit match on my cheek, leaving a lifetime mark; next, a neighbor pushed me from a chair I had stepped on— perhaps to claim some kind of power over her—and I hit my mouth against a table, shattering my two front teeth.

See, Elena— I am talking to you now— I had forgotten all that: I forgot the long record of scares and threats that had been mine, my sister’s, and my girlfriends’, against which our mothers, and their mothers before them, had no antidote, but only a list of warnings that scared us even more. It was a war outside our houses and we didn’t know; we were just fighting it. It was the primordial war of the elements against us, of men against women, of fathers against mothers, of fathers against daughters, of daughters against the world; of us—little women—already against ourselves.

Elena, thirty pages in, and you pulled me back into all the wars I didn’t know how to fight. When your girls climbed the stairs toward the greatest of their terror and knock at Don Achille’s door, I turned my gaze away. I didn’t want to see the man’s face. I didn’t want to hear his words. I didn’t want to see the girls’ defeat. I stopped reading. Elena and Lila “were climbing toward fear, to interrogate it,” and I was descending, quickly, into the past, and I did not want to interrogate it, nor did I want it to interrogate me.

Why did you take me there? Who told you so much about me?

You gave him the name of Don Achille, but I know him. It’s Don Vincenzo. I remember him, his plastic bags, and his dirty fingers and yellow teeth. He didn’t live in the building across from us, he lived right next door. I remember his smoker’s cough; I hear it again, right here, now, in my ear; did he come to live next door again? Didn’t I leave him behind? Along with his smell of cigarette and sweat hanging in the elevator, on the landing—sometimes hanging in my own house after he visited my mother, the widow next door. One cannot hide from their own smell. I smelled him, and I knew he had come to pay a visit to the widow next door. He bought her cigarettes and gum and whoknowswhat. He carried them in his plastic bags. In his house next door, he smashed chairs, punched tables, and shouted curses and obscenities at his wife and kids, then slammed the door. And when he slammed his door, I was afraid he would knock at mine, and that my mother had to open it. See, Elena, I’m going to turn away again now. Because I wasn’t Lila then. Lila would have pointed a knife at his throat, right?

But perhaps Don Vincenzo was not your Don Achille. He was not a camorra boss, he owned nothing but his plastic bags. Perhaps Don Vincenzo was your Donato Sarratore, the railway worker who wrote cheesy love poems not for his wife but for his downstairs neighbor, Melina the widow, and made her lose her mind.

Or perhaps your Don Achille was Sandokan, the little camorra boss of my rione. People called him Sandokan because of his long dark hair and beard, and a scar on his face that, rumors said, he had gotten in jail. He sat on a tall chair at the corner of the subway station overseeing his business of pirated music tapes and smuggled cigarettes that he kept in crates hidden under the music stand. My mother sent me there to buy three packs of Merit that would be gone in one day.

A flock of men and boys, perhaps his children or nephews or cousins—an entire Sandokan’s tribe—was perched on the subway stairs, on the stools behind the music stand, laughing, smoking, stripping every woman and every girl out of their clothes with their gaze. I made sure to be overdressed every time Mamma sent me to buy cigarettes so that once the men in the rione had peered through my clothes, layer after layer, they still couldn’t see me.

But, Elena, you saw me. Now, you bring me there again. I am overdressed and hot, red in the face; I voice my cigarettes request in Neapolitan dialect to sound tough.

“Tre pacchett’ e’ Merit,” I say; but my Italianized Neapolitan against the curt, often obscene language of the street vendors, shames me, bares me despite my too many clothes. My imperfect dialect is another sign that in my daily battles against the rione I will always lose.

“Let’s give three Merit to this bella piccerella,” Sandokan repeats mocking my dialect. He hands me the cigarettes, his fingers fondle my hand, his palm is slimy like the Christmas eels I was so afraid of touching in the kitchen sink before they got slaughtered. I give him money, careful not to touch him back, he gives me change, and rests his fingers in my palm too long while singing a languid love song.

He clutches my wrist with a smirk on his face, “Ciao Bella,“ he says.

I learned then that this greeting I’d hear from strangers hundreds of times in my life would never be innocent.

I don’t say goodbye, I turn away and leave hastily with three packs of rage in my pockets. On their label it’s written “Il fumo uccide”—“Smoking Kills.”

I swore to myself on those uncountable short walks to Sandokan’s stand from home, back and forth, that I would never smoke in my life. And, Elena—I know that you know—it’s not because smoking kills.

What else do you know? Too much. All the dark secrets and all the hidden truths that you spell without mercy and without solace.

In the book that that day I decided not to read, there was too much of Neapolitan men and women I knew so well, too much of Neapolitan mothers, of their own mothers and their daughters, a genealogy of women I came from, and whose story or destiny I wanted to change — starting with my own.

It was not until the third volume, Those Who Leave And Those Who Stay (in Italian literally “Those Who Escape”), that I began to be intrigued again. I was one of those who left, hence one who often wondered about the other life not lived, if she had stayed. Again and again, I felt I belonged to the books, that somehow, somewhere, Elena the writer was telling also part of my story.

I began feeling ready to return to her writing to interrogate my possible future. Yet I waited for the publication of the last volume, four years later, to read all of them at once. I needed to know how it all ended, have the reassurance of a complete life, the hindsight, the perspective of distance, although reassurance never comes in Ferrante’s books, and one never feels safe.

But one thing I learned for sure: that reading about the life that came close to being yours, the one you eluded and didn’t choose, is more powerful than reading about the life that looked like yours.

And if reading the four volumes all at once was also a journey through a dangerous zone filled with traps, I had done the right thing to wait: I had to first begin writing more of my story in a new world before reading about the one I left in the old one.

At the end, I finally knew: I had been half Elena and half Lila, and I had been neither of them.

My goodness. I was literally out of breath as I read this essay. I feared where I was being taken, and like Sara felt about Ferrante, I didn’t want to know about dark and painful incidents the writer experienced as a child.

Ferrante is a brilliant author and Sara Marinelli matched Ferrante”s brilliance in her essay.

Hello, Sara Marinelli here, author of this piece. Since some close friends asked me about my teeth accident that I mention in the story, I thought I would reassure readers publicly: thank God, those were my milk teeth!

Swooning ~ Caitlin and Joy